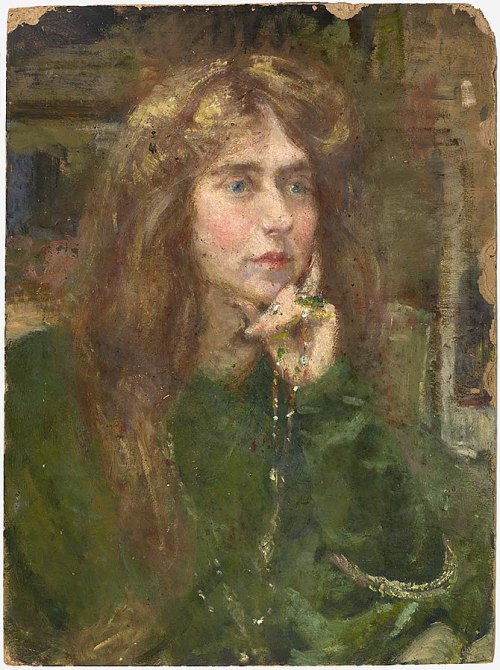

Alice Pike BarneyNatalie at Seven, 1883 / Natalie and Missa, 1890 / Natalie Barney in Fur Cape,

Alice Pike BarneyNatalie at Seven, 1883 / Natalie and Missa, 1890 / Natalie Barney in Fur Cape, 1896 / Natalie with Necklace, c. 1900 / Lucifer, 1902Some of the paintings that Alice Pike Barney (1857-1931) made using her daughter, Natalie Clifford Barney (1876-1972), as a model. “As the year [1900] closed, the fallout from Quelques portraits-sonnets de femmes [Natalie Clifford Barney’s lesbian poetry collection] caused a major break in the Barney family. It had taken months for word of the book to develop a strong buzz, but by now many people had read or at least heard about it. Natalie had been dropped by a few Washington society matrons, meaning that they refused to receive her in their homes. At least one family friend approached Natalie that summer, begging her to give up, for the sake of her parents, the course on which she was headed. In response to her critics, Natalie claimed that she didn’t care whether or not Madame so-and-so deigned to greet her on the street. As she once said of Colette’s first husband, Willy, “Not everyone is capable of knowingly creating a bad reputation for themselves.”There was a certain hypocrisy to the way Natalie was treated. […] Discretion (or, if you prefer, sexual hypocrisy) was considered a duty. Among Natalie’s past and future conquests were socialites who, though they preferred the embraces of women, led ostensibly “normal” lives. As long as they married, had children, did charitable work, and managed fine homes, nobody much cared what they did behind closet doors. In the end, Natalie’s greatest sin was not that she was a lesbian, but that she refused to be quiet and ashamed about it. One day, Albert Barney [her father] picked up the society gossip journal Town Topics and read a small but fatal headline: Sappho sings in Washington. With that single headline, his world exploded. Highly intelligent and far from naive, his suspicions about his beloved daughter had long ago turned to certainty. The Town Topics piece, entwining his daughter’s name with that of a perverted Greek harlot, fulfilled his worst nightmares of scandal. The fact that his wife had contributed the artwork to Natalie’s book [three of the four women who modelled for her were her daughter’s lovers] constituted a double knife thrust to the heart. How, he wondered, would he ever live this down? The timing and exact circumstances of what happened next are impossible to pinpoint. The entire episode wasn’t one that anyone in the family wished to remember, let alone document. It’s telling that Alice, who scissored from the newspapers each mention of her girls for permanent inclusion in her scrapbook, didn’t bother to keep the big Sappho Sings article. What is true is this: Albert stormed into the editorial offices at Ollendorff in Paris to buy, and then destroy, the remaining copies and all printing plates for Quelques portraits-sonnets de femmes. His action doubtless accounts for the book’s extreme rarity today. He then brutally pulled the blinders from Alice’s eyes about the meaning of the poems in Quelques sonnets. He berated her ceaselessly, and would until his death, for having so naively contributed paintings of Natalie’s lovers to the book. The revelation about Natalie’s sexuality stunned Alice. The evidence had been there for years, obvious to all, but she had been in complete denial. Now, forced to accept the truth, she was shocked and sickened. For perhaps the first time ever she was unable to apply the laissez-faire philosophy that had defined her approach to life. In early January 1901 the Barneys boarded a ship to New York, leaving Natalie behind. Though weakened by illness, he constantly lambasted Alice, enumerating her countless sins, the greatest of which was the evil inherent in Natalie’s character. As usual, she endured the abuse by politely ignoring him. Deep within, however, she was awash in conflicting emotions. She loved and admired her daughter, but was horrified by her lesbianism. Late in January, she made her feelings clear in a letter that must have devastated Natalie: It has come at last. Your father is quite crushed by this and really very pathetic. How perhaps you, through your disregard for us and your callousness, may remember my disgust when you would speak of this forbidden sin—and realize that every right-minded decent person is condemning you and us—as they would of the greatest evil… I am too sick and ill to write more. I used to feel sorry for Mrs. Hoy when people said things of Mattie—and how small her sin was—if true—compared with yours, which you broadcast about, as if being evil is not bad enough. But you must in every way, to every person, make yourself a horror and a danger… Your only chance to redeem yourself is to change your life and writings and remember that in no way can you defend yourself—or reply to this [Town Topics] article… For there is not the slightest loophole. You have closed every escape. […] You have done a bad thing—a sin against law and mankind and I can only hope that your ideas have shocked and horrified instead of converting. It took months for Alice to accept Natalie’s nature, but eventually the truth brought mother and daughter closer. No longer engaged in subterfuge and lies, Natalie’s new relationship with Alice was easier, friendlier, and more honest. After her initial repugnance, Alice tried to see Natalie’s sexuality as simply part of her nature—a nature similar in many other ways to her own. “How much of myself I’ve passed on to you,” she wrote years later. “You’re cultivated and I—not—but we’ve got the same traits, grabbing here and there, dashing from this to that. So much of the monkey in us.” There would be many times in the future when Natalie and Alice didn’t get along, but at its heart their relationship remained strong and loving. Each took pleasure in the other’s accomplishments. “I’m terribly proud of you,” Alice would write; or “I can’t express my admiration, my child.” They would collaborate in writing plays, visit each other, and always, no matter where they might be, there were the affectionate letters. Only once, many years later, did Alice reveal the pain that Natalie caused her. It happened when Natalie made a casual observation. “Mother,” she remembered saying. “You have so happy a temperament that I cannot imagine anything that has ever been able to cause you more than a passing sorrow.” Alice drew back as if struck. She appeared embarrassed, and looked away. Natalie laughed, curious to know what could possibly have shaken her mother’s legendary equanimity, but Alice remained stubbornly and uncharacteristically silent. Growing uneasy, Natalie pressed for an answer. Alice hesitated, gazing back over the years to a moment of sorrow so great that it obviously pained her to recall it now. And then, slowly, she faced her daughter, staring with profound sadness into those ice-blue eyes. “You,” she muttered, almost as if speaking to herself. “You…’” — Suzanne Rodríguez, from Wild Heart: A Life, Natalie Clifford Barney and the Decadence of Literary Paris -- source link

Tumblr Blog : women-loving-art.tumblr.com

#artists#suzanne rodriguez