ladycashasatiger:history-of-fashion:1837 Henry Perronet Briggs - Portrait of the Duke of WellingtonI

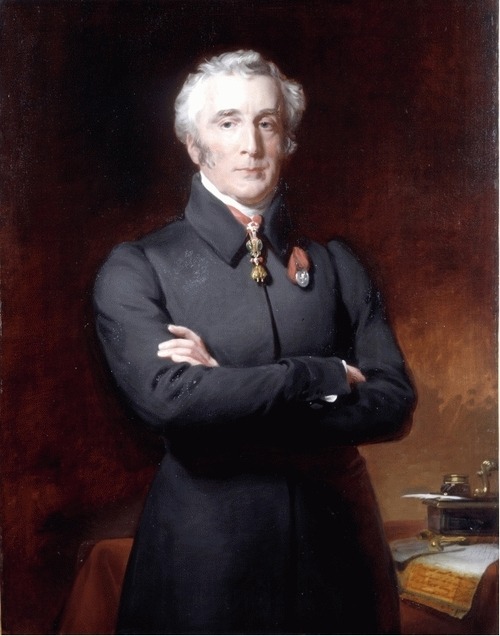

ladycashasatiger:history-of-fashion:1837 Henry Perronet Briggs - Portrait of the Duke of WellingtonI believe the following information has been lifted from The Iconography of the Duke of Wellington (Gerald Wellesley, 7th Duke, 1935), which is unavailable online. The original Briggs portrait commissioned by Francis Egerton (as mentioned below) may still have been at Walmer at that time, though I can find no record of it there now and do not recall seeing it there. The talents of Henry Perronet Briggs have been unfairly neglected in this century, as this accomplished and bold portrait of the Duke of Wellington demonstrates. The figure of the Duke looms out of the darkness, his personality and achievements expressed by the key elements on which the light falls. We are directed, without distraction, to his steady and uncompromising gaze, his Waterloo medal and, around his neck, the Order of the Golden Fleece — a unique appointment for a subject of a Protestant nation — which expressed the gratitude of the Spanish and the Austrian royal families for his work in saving them from Napoleon. The Duke’s solid pose with folded arms serves to underline this sense of undaunted resolution.Although this portrait is not the only version of this composition, it is significant in being the only version to depict an inkstand in the foreground, and a table on which there is a letter bearing the Duke’s signature. The paper is applied to the canvas, rather than painted in, and the handwriting upon it was confirmed by the late Lord Gerald Wellesley to be that of the Duke himself. This must be a fragment of a letter from the Duke to Winthrop Praed who commissioned the portrait, and is thus a unique link between patron and sitter, as well as an expression of the specific basis for the friendship of the two men.The first version of this portrait type, which was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1837, must be that now hanging at Walmer Castle, the Duke’s official residence as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. That version was painted for the Duke’s friend, the Earl of Ellesmere, and was intended to be an exchange between them, although the Earl’s portrait was not completed for some years afterwards. In addition, versions of the portrait were painted for others who were friends of the Duke, or who were well-thought of by him. Winthrop Praed, the aspiring Etonian poet, was among these, and his portrait would appear to have been given a special relevance to the sitter absent from the others. During a period of Opposition in 1833 the Duke had provided Praed with material for a number of articles attacking changes in the Ordnance Department. Wellington was impressed by the younger man’s dedication to a cause that he also fostered, and asked Praed to defend him in The Morning Post against an attack printed in The Times. In appreciation the Duke invited Praed to stay with him at Walmer Castle — which may have been the occasion for commissioning this present version of the Duke’s portrait there — as well as, undoubtedly, assisting him in his political aspirations. Little in Praed’s brief Parliamentary career suggests that he could have achieved such office as he did — he was appointed Secretary to the Board of Control during Peel’s four month administration in early 1835 — without such powerful patronage.This portrait is, therefore, peculiarly suited in character to the unassuming statesman and poet for whom it was painted. Alone of these portraits, for example, it creates the illusion that Wellington is portrayed in civilian dress, although closer inspection reveals the elegance of a general-officer’s frock coat. Yet it is a curiously flexible composition. A later version, painted in 1840 (Cutlers’ Hall, Sheffield) and engraved in 1842 extends the figure to full-length and adds a military cloak and a horse and groom in the background to create an uncompromisingly, even theatrically, martial image. But here the muted tones and calm understatement maintain a more plausible authority, and do much to suggest the implacable authority of the Duke of Wellington that made people so ready to follow his bidding. The final touch of the inkstand and letter immediately recall the literary and epistolary foundation of the Duke’s friendship with Praed, and with the attachment of an autograph letter from the Duke, prominently bearing his signature, add an unexpected note of intimacy to such a formidable icon.In his own time Briggs was respected for his abilities: as ‘Baron Briggs’ Thackery places him first in his ‘List of Best Victorian Painters’ (Fraser’s Magazine 1838). His career had begun early, and he published two engravings in the Gentleman’s Magazine while he was still at school. By 1811 he had entered the RA Schools, and two years later he was established as a portrait painter in Cambridge, where his work is represented in a number of colleges. He returned to London over a decade later, where he encountered the still-lingering mystique of Reynolds, and made copies of a number of his portraits, influencing his improved style of this period. Briggs died in January 1844 at the age of 51.(source) -- source link

Tumblr Blog : history-of-fashion.tumblr.com

#napoleonic