Motion in the ocean Plate Tectonics and earthquake hazard assessment has benefited hugely from the e

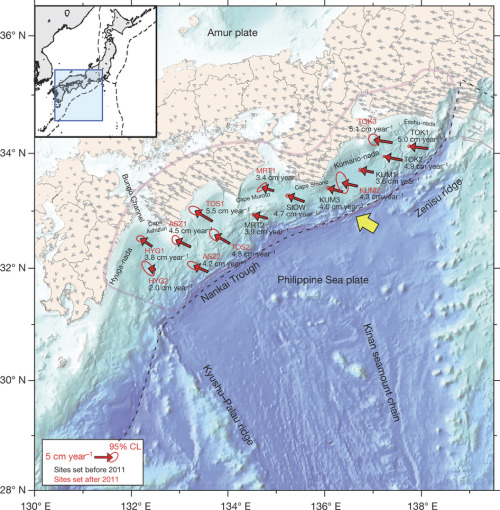

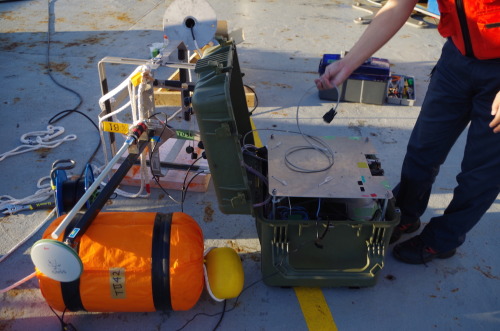

Motion in the oceanPlate Tectonics and earthquake hazard assessment has benefited hugely from the existence of GPS technology. Thanks to the global GPS network, scientists can put receivers on different sides of a fault, measure how rapidly plates are moving far from the fault, and locate areas on the fault that aren’t slipping along. These areas of the fault that aren’t moving with the surrounding plate are technically called “slip-deficit regions” – they’re the part of the fault that is locked, building up stress that will at some point be released as a sudden slip in an earthquake.While this technology has worked spectacularly on land, the past 12 years has seen enormous devastation from earthquakes in the ocean, off the coasts of Sumatra and Japan. Unfortunately, GPS is much tougher to use on the ocean floor since a GPS receiver on the ocean floor won’t receive a signal from space. Both of those earthquakes occurred in areas that scientists didn’t anticipate slipping in the near future, so deploying GPS technology in the ocean to identify locked portions of a fault will literally save lives.The technique to do these measurements was initially developed over 2 decades ago by scientists at Scripps Oceanographic Institute, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and the Geological Survey of Canada. You’re actually looking at one about to be deployed; it’s called GPS/A – for GPS acoustic. Doing these measurements in the ocean requires 2 pieces of equipment. First, place a GPS receiver at the Earth’s surface to record a fixed location, then place an acoustic receiver in the ocean that measures the range to the fixed GPS station by receiving and transmitting sound pulses through the ocean water. While the presence of two measurements rather than one increases the possible error they can still successfully measure plate motions as the errors are on the order of millimeters and plate motions are centimeters per year. The costs of maintaining the stations are high since one has to be on the ocean floor, but the potential benefits are clear.Japan, which suffered a direct hit from the 2011 Tohoku quake and tsunami, has deployed 15 of these arrays on the ocean floor near the Nankai trough, the subduction zone that propagates south of Tokyo.At this subduction zone, the Philippine Sea plate is approaching Japan at a rate of 6.5 cm/year. Some areas of the upper plate are deforming at rates over 5 cm/year in response; these areas are the locked portions of the megathrust fault. Other areas are deforming at less than 3 cm/year; these areas can still move in a large earthquake, but they are accumulating less stress and thus are at lower risk of being the epicenter of a large earthquake and tsunami.Several of these fault patches have ruptured in recorded history, but others have not, indicating they could be at risk of earthquakes in the near future. Continuing to monitor the motion of these patches will help scientists estimate the size of quakes they may drive and better simulate the tsunami wave heights they could create.These measurements have also provided insight into the operation of the subduction zone itself. The Nankai trough includes several areas where seamounts – submerged areas of thickened crust that were likely once ocean islands. These measurements show that those areas are moving more easily than the rest of the fault, meaning that in this megathrust, subducting an entire island actually makes the fault weaker and reduces its ability to trigger a major earthquake.-JBBImage credits:Cires/CU Boulderhttp://ciresblogs.colorado.edu/hobitss2/2015/06/27/gps-acoustic/Original paper:http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v534/n7607/full/nature17632.htmlTechnique announcement:http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031920198000892Press releasehttp://bit.ly/28Vl47v -- source link

Tumblr Blog : the-earth-story.com

#science#japan#fault#engineering#research#geology#megathrust#tsunami#geohazard#acoustic#crust#plate tectonics#nankai