greatleapsideways: It’s interesting to consider these portraits in relation to Richard Avedon&

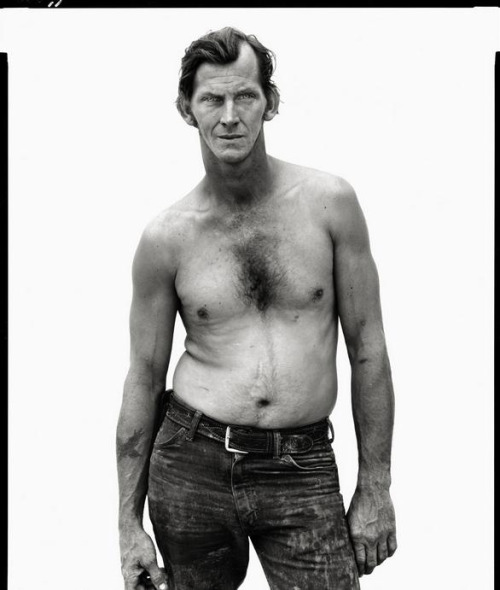

greatleapsideways: It’s interesting to consider these portraits in relation to Richard Avedon’s famous statement in the foreword to In The American West (1985),and then in relation to an argument Julian Stallabrass set out in an essay on portraiture published twenty-two years later. Avedon wrote: “A portrait photographer depends upon another person to complete his picture. The subject imagined, which in a sense is me, must be discovered in someone else willing to take part in a fiction he cannot possibly know about. My concerns are not his. We have separate ambitions for the image. His need to plead his case probably goes as deep as my need to plead mine, but the control is with me.” Latterly, Katy Grannan has most overtly developed the formal model of Avedon’s portraiture, first in Boulevard (2010) and most recently in The 99 (2014). It seems very necessary to note that this latest work began when Grannan set out to retrace a region of California photographed by Dorothea Lange during The Great Depression (see More American Photographs). Questions of hardship and the political complexities of photographic representation are thus intricately interwoven in the fabric of these new images. Stallabrass makes a persuasive argument about the profound influence of consumerism, political disenfranchisement and the spectacular nature of contemporary culture on the changing conventions of the portrait. In an essay centred around Rineke Dijkstra’s Beach Portraits, and the advent of a conventionally neutral expression in portraiture printed at a large scale, he writes: “This constitutes the terrible plausibility of these images, and part of the basis for their success: they do describe and also enact a world in which people are socially atomized, politically weak, and are governed by their place in the image world. In demanding that the maximum visual detail be wrung from their subjects, they silence and still them. In their seamless, high-resolution depictions, they present the victory of the image world over its human subjects as total and eternal. While the results may hold apparently radical elements – that the passivity and image victimhood of the subjects may rebound on their viewers – the ambiguity of such images finally salvages artist and viewer. Such images oscillate between identification and distancing, honoring and belittling, critical recognition and the enjoyment of spectacle, and access to the real and the critique of realist representation. (…) Why are subjects of contemporary art so often taken as mere spectacular fragments rather than as active persons, while the opposite is assumed of its makers and viewers? Even in the apparently opposing participant-observer mode, there is little stress on agency (other than entertaining misbehavior) bur rather on passive conditions that are meant to constitute assured identities. In both, the excluded middle is agency and its depiction in documentary, along with the construction of a realist structure through the combination of differentiated images, and particularly the idea that identity might be transformed through agency. The plausibility of the ethnographic strand of photographic imagery surely derives from the accuracy of its implicit view of neoliberalist societies. The push and pull of identification and distancing, and honoring and belittling, are staged only at the level of the image, not in seeing its subjects as agents. In this sense, such images exhibit a transparent complicity with commercialized spectacle. There is a link, in other words, between the presentation of these subjects as mere image and the familiar powerlessness of people in day-to-day democracy, of image and news management, of the hollowing out of citizenship in favor of consumerism, of broadcast and celebrity culture. This [ethnographic] strand’s relentless focus on the fixed image is a reflection of the marked decline in political agency, in democratic participation, which is a steadily growing and universal feature of neoliberal societies.” — Julian Stallabrass, in the essay What’s In A Face? Blankness and Significance in Contemporary Art Photography, October Journal, Fall 2007 All photographs © Richard Avedon, from In The American West -- source link

Tumblr Blog : greatleapsideways-deactivated20.tumblr.com