Taking up space: The Lady Members’ Room.Rachel Reeves MP for Leeds West is one an incredible l

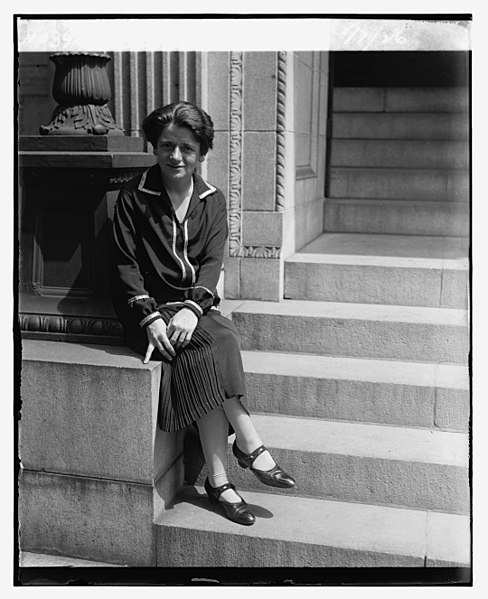

Taking up space: The Lady Members’ Room.Rachel Reeves MP for Leeds West is one an incredible line up of people participating in our Women and Leadership: A Symposium on 17 May that also includes Dr Farah Karim-Cooper (Shakespeare’s Globe), Claire Van Kampen, Morgan Lloyd Malcom, Professor Liz Shafer (Royal Holloway), Dr Sumi Madhok (LSE), Winsome Pinnock, Dr Will Tosh (Shakespeare’s Globe), Baroness Kingsmill CBE, Rachel Reeves, Stella Kanu and Gillian Woods (Birkbeck). They will discuss women in history, their own experiences in leadership roles, the pay gap, ‘likeability’ and what kind of leadership do women or ‘should’ women cultivate?This blog is an extract from Rachel Reeves’ book Women of Westminster in which she gives insight into the Lady Members’ Room in the 1920s. ‘I find a woman’s intrusion into the House of Commons as embarrassing as if she burst into my bathroom when I had nothing to defend myself, not even a sponge,’ Winston Churchill famously quipped to Lady Astor. She rebuffed him with a wry smile: ‘You are not handsome enough to have worries of that kind.’ Yet Churchill’s attitude was typical of male views towards women in Parliament.Westminster was, and remains today, a male-dominated institution. Charles Barry, who designed the Houses of Parliament, had designed a number of male-only private members clubs; in many ways Parliament was just another club with a debating chamber appended to it. The physical barriers to women’s acceptance within Parliament were particularly pronounced in those early years of women’s representation. The scarcity of the new women MPs, combined with institutional sexism, meant that they were often made to feel unwelcome in the Commons. There were numerous cases of women MPs being mistaken for secretaries, as well as generally being treated with distrust and a continued sense of disbelief at their very existence.56‘The dungeon’ The Lady Members’ Room, a designated room where women MPs could respond to correspondence and dress themselves, served as an office for all women MPs. Known as ‘the dungeon’, it was a small, stuffy room in the basement of the Palace of Westminster. Mark Collins, Parliament’s estates archivist and historian, described it as ‘a dark place with wooden panelling.’57 When Wilkinson first entered the House in 1924, the nearest ladies’ toilet to the debating chamber was a quarter of a mile walk, along three long corridors and two flights of stairs.58 In 1929, the Lady Members’ Room was moved down the corridor to accommodate the larger pool of women, but it was still small and lacked a changing room or an annunciator to alert MPs as to what was happening in the debating chamber. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the facilities were improved. Meanwhile, male MPs had a much greater purchase on the space of Westminster. Unlike women, male members had access to baths (particularly useful during all-night sittings) and dining rooms. Ministers (almost exclusively male) had their own offices, and not even Nancy Astor dared to enter the smoking room, ‘where a whispered word may sometimes have more effect than an hour’s speech thundered in the debating chamber’, as Ellen Wilkinson described it.59 The physical infrastructure both facilitated, and was facilitated by, elite social networks. In almost a physical extension of the parliamentary estate, male members would go to their private male-only clubs (including the Athenaeum, the National Liberal Club, the Garrick and the Carlton) to discuss politics. ‘I am not a lady – I am a Member of Parliament’Ellen Wilkinson was the first woman MP to enter the smoking room. As she bounded up to the door, she was stopped by a policeman who informed her that ladies did not usually enter. ‘I am not a lady – I am a Member of Parliament,’ she responded peremptorily as she opened the door. Wilkinson continued to push the boundaries of Westminster convention. In 1928 she used her position on the Kitchen Committee (a select committee dedicated to the domestic arrangements of the House of Commons) to initiate a campaign for women to be admitted to the Strangers’ Dining Room. As it stood, while male parliamentary secretaries of ministers and opposition leaders could eat in this cheaper dining room, women had to eat in the more expensive Harcourt Room. Despite opposition to Wilkinson’s campaign from others on the committee, including her only other female colleague (Mabel Philipson), the motion passed. The speaker decided that a lady guest could be admitted for dinner, but not for lunch, on the dubious grounds that there was a shortage of accommodation. Astor intervened, saying: ‘Do not women need luncheon, too?’ Nevertheless, this was primarily a moment of celebration and Wilkinson entertained a party of female guests in the Strangers’ Dining Room (a meal which was, interestingly and unusually for the time, a vegetarian and non-alcoholic affair). But she continued to push forwards, and when appointed to the committee once more in 1930, she was active in the campaign to admit women for lunch as well. In October 1931, Labour MP Edith Picton-Turbervill made a request for a women’s dressing-room, which was granted in the next Parliament. Women were beginning to ‘take up space’. Women and Leadership: A Symposium takes place at Shakespeare’s Globe on 17 May.Image: Ellen Wilkinson MP in 1926. Source: Library of Congress. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : shakespearesglobeblog.tumblr.com

#parliament#politics