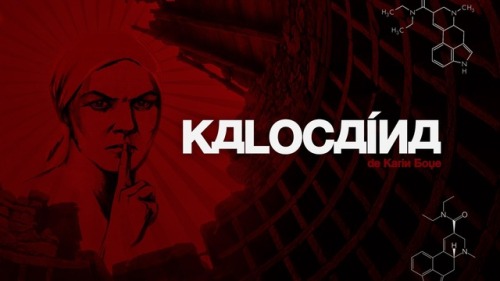

(Images: top, from a cover illustration of a translation of Boye’s Kallocain; below, left Zenta Maur

(Images: top, from a cover illustration of a translation of Boye’s Kallocain; below, left Zenta Mauriņa, right Karin Boye)Zenta Mauriņa was a Latvian writer, literary critic and academic (in philology), who lived in Sweden during the postwar period. In her essays she wrote about many writers, particularly Latvian, Russian, German and Swedish. Here is a translation of her thoughts on prose - particularly the sci-fi novel Kallocain - by the Swedish poet and novelist, Karin Boye. The extract of an essay, under the cut, is translated from the Latvian original, appearing in Zenta Mauriņa’s Spīts Esejas, 1947.Karin Boye - Divine DisquieterIn her relatively few stories and novels, one can clearly hear the gentle schoolteacher’s voice: “One thing we all know for certain: for anything to grow, there is a need for warmth and love. Not as a wage, but freely, unweighed and unmeasured. Without reason.” (from her novel Merit Awakens, 1933) She expressed herself most fully in her science-fiction novel Kallocain (1940). Just like Franz Werfel in his final novel The Star of the Unborn, and in Hermanne Hesse’s The Glassbead Game - though we don’t know if that will remain his last novel - Karin Boye expressed, shortly before her suicidal death, her thoughts in her novel of events set beyond the 20th Century: so much antithesis did these writers feel towards contemporary society. Kallocain is a bitter denouncement, a despairing cry. Look, this poet says, if this is how the world is, then I decline to live in it. The novel is set in the intellectually constructed Chemical City No.4. The inner life of people has been stopped. No-one trusts anyone, no-one recognizes the wonders and terrors of self-discovery, nor the struggles of their closest partners. Each is an absolute stranger to another. All live by ready formulas, but deep, deep within their remains a need to cry out, and to trust. But the chemical city inhabitants can only express this if they receive an injection of green (symbolising vitality) poison, then their shrivelled inner-world refreshes. Human estrangement, exhaustion of creative strength, a lack of compassion, and soullessness, all expand to tragedy. In this novel, as in many of her prose compositions, there is not much action. The characters are abstract, created only in order to express the author’s thoughts. In this respect she is the opposite of Bergman, who depicts the lowly people, and weaves them as if into a linen cloth, but showing the juicy life of each thread. Kallocain is her most personal work, filled with a terrible dread for humanity’s future. She dreams the dream, that the world could be saved, if mothers led and organised all important concerns. The poet is not thinking so much of women with children, but of a motherly principle, that is, to protect and preserve life. According to her thinking, this motherly principle could also extend to a man, and they would be those men who can be safely trusted. Only the daring mother, who is conscious of every living creature, could transform the waste heap of the world into a fertile abundance. But Karin Boje had no hope of achieving her dream: at the age of 40 she committed suicide, over whose reason much has been written and speculated. This act of hers is especially striking for us, knowing that she lived in a land spared the storms of destruction, and her life was free of major illnesses or personal tragedies. Her thoughts were bright, and her heart was bright, she loved people, but she had no place to cast an anchor. - Zenta Mauriņa (1947)Translator’s notes:The Glass Bead Game did prove to be Hesse’s last novelBergman refers to Hjalmar BergmanIf you read a free online English translation of Kallocain from the University of Wisconsin -- source link

Tumblr Blog : bourbakiaxiom.tumblr.com

#karin boye#zenta maurina#swedish literature#latvian writing#witmonth#mytranslation