theculturedmarxist:peashooter85:The Death of LondonHistorians today mostly shirk from using the term

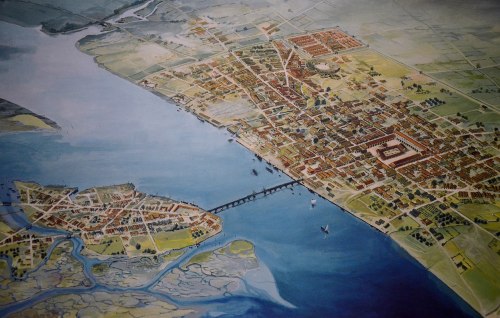

theculturedmarxist:peashooter85:The Death of LondonHistorians today mostly shirk from using the term “The Dark Ages” when describing the period of European history after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. After all in the rest of the world things were going quite well. Civilization was flourishing in places such as China, India, the Middle East, and Central America. The remaining Eastern Roman Empire also thrived with Constantinople becoming one of the largest and wealthiest cities in the world. However, for much of western Europe and Italy, things really did get pretty dark. As the Roman Empire declined and crumbled so too did the cities and infrastructure of western Europe. Since before the times of Diocletian the lot of the average Roman pleb grew worse as the Roman middle class disappeared and poverty increased. The increase in poverty resulted in less wealth to maintain public works and infrastructure. By 5th century many public works, roads, and buildings were decaying and crumbling from lack of maintenance. The decrease in wealth and decline of public infrastructure also led to a collapse of trade, further decreasing the wealth of the empire and making it less profitable to work in skilled trades. Urbanization decreased as unemployed people could no longer make a living in big cities, especially port cities which were suffering as a result of decreased trade, and thus they left the cities looking for work in the countryside, often as peasant farmers. All over western Europe the population of cities declined drastically. Add in barbarian invasions and warfare, which made the situation even bleaker.Perhaps one of the hardest hit provinces of the former empire was Britain. By the mid 4th century public infrastructure was already beginning to deteriorate and by the 5th century the population of British cities declined significantly. To learn more about this period I would suggested listening to the “Decline of Civilizations” podcast episode on post Roman Britain. A prime example of this decline is the city of London, or as it was called in ancient times, Londinium. Established in 43 AD London had become one of the largest and most important cities in the province as it was a bustling port city and commercial hub. By the 2nd century AD it had a population somewhere around 30,000 to 60,000 people. With the Antonine plague and the crises of the 3rd century the population began to decline. By the time Britain had made a Brexit from the empire in 410, the population was around 10,000. Archeological evidence shows that in large sections of the city buildings and houses had been raised and converted into farmland, pastures, or simply left as empty lots. By the mid 5th century a small number of wealthy families continued to dwell in what was essentially a gated community surrounded by the ruins of a dying city. By the end of the 5th century, London was an empty ruin. Essentially, the city entirely ceased to exist, population zero.For the next century or century and a half London would remain an empty ruin. In the 7th century the city was refounded by the Anglo-Saxon as “Londonwic” although the Anglo-Saxon city was located outside the walls of the Roman ruins. It wouldn’t be until the 9th century during the reign of Alfred the Great that people would settle within the Roman walls of the old city and it wouldn’t be until the mid 14th century that the population of London would recover to what it was in the 2nd century.Gibbon, […], has imposed upon us by sheer intellectual authority the concept of the ‘decline and fall.’ What, if anything, does decline mean in this context? ‘The Late Antique period,’ it has been said, ‘has too often been dismissed as an age of disintegration … No impression is further from the truth. Seldom has any period of European history littered the future with so many irremovable institutions. The codes of Roman Law, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, the idea of the Christian Empire, the monastery …’ Our own intellectual traiditon makes us judge Late Antiquity by the standards of the early Empire (what the French call, revealing the ‘Haut-Empire’). The late Empire is judged to be in decline because it does not come up to the same standards. Although Paulinus of Nola writes one of the loveliest lyrics of all antiquity (’I, through all chances that are given to mortals’—ego te per omne quod datum mortabilibus), and the the first great Latin hymns of the Christian Church trample across the centuries to the rhythm of the marching songs of the legions (pange, lingua, gloriosi proelium certaminis, like the song about Julius Caesar, the ‘bald adulterer’, which his soldiers sang at his triumph ecce Caesar nunc triumphant …, Suetonius, Julius Caesar 49), nevertheless they are not part of the classical canon. The towns ‘decay’—the baths fall out of use, the temples are deserted, the forum ceases to be the centre of civic and commercial activity, and we assume that the cause is economic. The bars so frequent in Pompeii and Ostia seem to disappear. But in fact many of the changes are caused by changes values. The Christian Church opposed the amphitheatere, the threatre, the baths, the bars, which often served as brothels, and obviously the pagan temples, for moral and religious reasons. The rich ceased to spend their money on the beautification of their cities, as they would have done in the Antonine age, and gave it instead to the Church; Paulinus can serve as an example, who sold estates ‘like a kingdom’ and retired to be a simple parish priest at Nola. The rich lived far more on their estates, and if the town property that they left vacant was sub- and sub-sub-divided for the poor, we should not forget that in the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century London the slums were largely made up of middle- and upper-class houses, sadly decayed, in which many poor families lived. Indeed the familiar contemporary problem of the decline of the inner city, which is what the late antique city also suffered from, is not caused by an absolute decline in the economic health of our society, but by a shift in the distribution of economic resources. In 1881 Brixton was peculiarly ‘genteel’, ‘a suburb for the wealthy tradesman’. If it is ‘genteel’ no longer, that is because the wealth is now invested elsewhere. This is not to deny that the later Empire suffered from a genuine economic crisis […], but the concept of ‘decline’ requires closer examination. Paradoxically, we might have found ourselves more at home in the early Empire, pagan though it was, than in the Christianized late Roman or Byzantine city. The influence of ‘classical culture’, its values as represented in literature, the visual images of its art and architecture, even the tone of its conversation and its jokes, to judge from the examples given by Macrobius, for instance—all this affects us and is more familiar to us than the wholly different value-system and social environment of Late Antiquity. This is why Gibbon was so successful for so long in imposing his own conceptual framework on the study of the relationship between the early and the later Empire, and why his judgement on the Antonine Age, […], has had so long a run.—The Roman Empire, Colin Michael Wells.I’m sorry but I’m just not buying the whole idea that the fall of Western Rome didn’t cause a drastic upheaval of western Europe. It wasn’t just baths, theaters, forums, and pagan temples that went in disrepair and disuse but important civic infrastructures like roads, ports, sewage, and sanitation. There wasn’t a decline of inner cities but a decline of urbanization in general. The proof is in the drastic shrinking of cities in the period between the 5th century and the 7th century. Paris went from a population of 80,000 to a population of 20-30,000. Lyon went from a population of 50,000 to around 10,000. Cologne went from a population of 30-40,000 down to a population of 20,000. Milan went from a population of around 100,000 to 30,000. Rome went from a population of 800,000 to around 100,000 which is a whopping decline. By the 8th century there were more seats in the Colosseum than there were people living in the city. London for a century went population zero and ceased to exist. This was at a time when the populations of cities around the rest of the world were significantly increasing. This is an extremely drastic decline in urban population that rivals the decrease of populations during the Black Death. We are talking about entire cities being left abandoned or nearly abandoned. I find it extremely hard to believe that this population decline was mostly caused by a shift in economic resources resulting from a cultural change. I also find it hard to believe that Christianity was behind that culture change as cities in the Eastern Roman Empire continued to rise in population (at least until the Justinian Plague would do its thing) while international trade and commerce thrived and infrastructure and public works expanded or remained intact. There was obviously a very hard shock to the economy of western Europe that would have been a major upheaval of society. Sure it was a redistribution of resources but it would have certainly led to very hard times for the average person. When people are abandoning major cities by the tens of thousands something very wrong is happening. Finally while Gibbons may have been wrong about many things when it comes to the fall of Rome, I earnestly believe that the pendulum of historic thinking is swaying way too far to the opposite extreme. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : peashooter85.tumblr.com