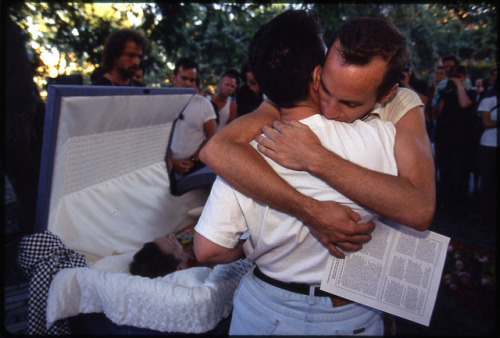

enoughtohold: It was impossible to touch my friend Jon Greenberg at his funeral in Tompkins Square

enoughtohold: It was impossible to touch my friend Jon Greenberg at his funeral in Tompkins Square Park, I said [in a draft of an unpublished article], in the middle of July [1993]. Too many people were standing in a crowd around him. His body was embalmed and it was on display in an open coffin underneath a shady tree near a volleyball net, where teenaged boys were tossing a ball back and forth. Death is as intimate as sex and today it was also public, as we watched each other go to his body with offerings, flowers, kisses, strings of beads. He was putty colored and he looked like he was staring, though his eyes were closed. A Radical Faerie in death, which ought to be a contradiction in terms, he was dressed in a floral shirt that just covered his nipples and tight purple trousers that disappeared into the closed half of his coffin. His death was especially painful, I said, because he was not an intimate friend. He was one of the people who make up the frame around my life, and who are important to me because we hold each other in place. Without him, I feel unhinged. I knew him from ACT UP. We were arrested together. Once we were both guests on a Jersey cable TV show about AIDS activism. The last few times I saw him were in passing, on the street, when we briefly stopped to talk. He lived a few blocks from me, and it felt safer, somehow, to be here, when he was. I have no idea how he made money, or who took care of him or tucked him in at night, or whether anyone did. He wandered fluidly from one moment to the next, as if the laws of cause-effect did not apply to him. Even his body, long and angled and lean, seemed to defy the earth’s gravitational pull. I never believed until the morning I got the wake-up call that he would die, fighting for his life in a hospital bed, ravaged by meningitis. The last time I saw him, I said, in another draft, his skin was dried severely, but his eyes were lovely, and I told him he was handsome, which was true. He went from being functionally sick to really sick, and he died after fighting AIDS every day for two years. He died with a lot of his ideas about death and disease floating around lower Manhattan on Xeroxed sheets with titles like The Metaphysics of AIDS. He died believing that the body succumbs to a virus because it can’t or won’t process the useful information that HIV contains. Love your virus, he said. “What is he talking about?” my friend Dave said, who’d graduated with a degree in pure math — “not applied, never say applied, please, casta diva, it was pure math” — from MIT. “AIDS is like the UPS guy with a package you haven’t learned how to unwrap? Or sign for?” We carried his coffin in a public procession up First Avenue, that day, I said, in every draft. From Houston Street, where Karen Finley’s poem “The Black Sheep” was cast in bronze and attached to a stone on the concrete traffic island separating Houston Street from First Street. We carried the coffin past Jon Greenberg’s apartment on First Avenue. Radical Faeries, and the Marys, his ACT UP affinity group, were playing pipes and drums and chanting over and over, “There is no end to life there is no end.” His parents from Michigan were neatly and comfortably dressed, his straight brother from California had a beard, and his gay brother from Manhattan was wearing Guatemalan shorts and smiling sadly. We had been asked to bring flowers and musical instruments, and people had roses hooked into their belts or tucked behind their ears or pinned to their collars. The coffin had come in a van and we unloaded it and went slowly up First Avenue. The blue sky was full of clouds and the sun cast shadows of the branches of the trees across the dome of the coffin. The pallbearers were in front with the body, marching behind a banner bearing Jon’s name and the dates of his birth and death from AIDS. People held hands in human chains to block traffic. We stretched the width of First Avenue, and turned at Seventh Street to Tompkins Square Park. There was a portable sound system in the Park and his brothers spoke. Somebody read from the Kaddish and his parents stood up and recited aloud, from memory. The volleyball game continued behind us, and young guys sitting on benches near Avenue B kept beating drums in the summer heat. Towards the end of the service, John Kelly, not in drag as Joni Mitchell for a piece of performance art, but in civilian drag, so plain he seemed naked, jeans and a t-shirt with suspenders holding his jeans up and his feet in combat boots, sang “Woodstock,” with the lyrics changed to mention the Park and drag queens and a cure for AIDS. […] Nothing is being done about this disease, is how they all end, and how this ends, punk rock ending, snare drum, E train stops at West Fourth, switch to the D, head home. I’m here, alive. Twenty years later. There’s still no cure. — John Weir, “Political Funerals,” December 2013. Photos by Thomas McGovern and Donna Binder. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : enoughtohold.tumblr.com

#hivaids