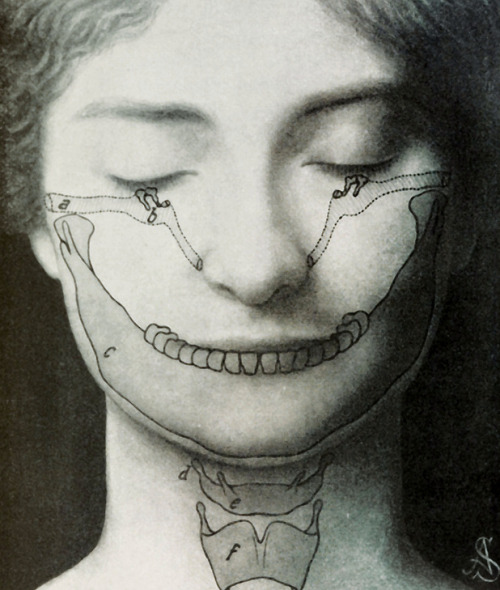

biomedicalephemera:Illustrations of the branchial (pharyngeal) arches in the humanTop: Adult female

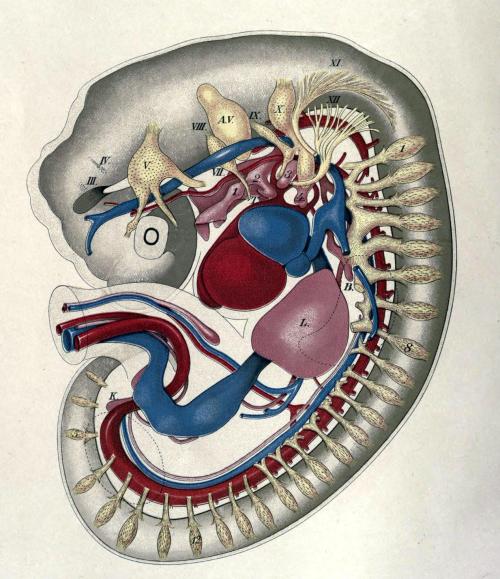

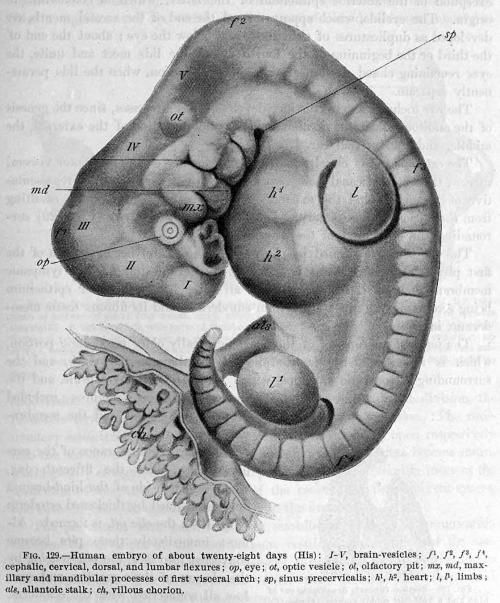

biomedicalephemera:Illustrations of the branchial (pharyngeal) arches in the humanTop: Adult female with fully-formed structures superimposed to show the adaptations present in humansBottom: 28-day embryos, external and internalWhen vertebrates develop, the pharyngeal arches are pairs of outpouchings in the embryo. In fish, they go on to form gills, and in other vertebrates they take many different forms. The different development paths of the pharyngial arches can tell us a lot about the evolution of vertebrates.All vertebrates start with basically the same form, and all have six pairs of mesodermal tissue lumps coming out of their crudely-developed tadpole-ish bodies. In humans, the pharyngeal arches appear in week 4 after fertilization. They then proceed to develop at different speeds, but their end forms are many of our neck and head structures.Every pharyngial arch has a cartilage stick, muscle component that differentiates from the cartilage, an artery, and a cranial nerve.———————————————————————The first arch is closest to the embryo head, and the numbering goes down the body from there.The first (hyomandibular) arch forms the maxilla, mandibular form (but not the mandible bone), incus and malleus (two of the three ossicles in the ear), auditory tube, muscles of mastication (chewing), trigeminal nerve, and external carotid and maxillary arteries.The second (hyoid) arch forms the muscles of facial expression, buccinator muscle, stapes (the third ossicle), stapedius (the smallest skeletal muscle, which stabilizes the stapes), part of the hyoid cartilage, facial nerve (VII), and hyoid and stapedial arteries.The third arch forms the rest of the hyoid, the thymus, inferior parathyroids, glossopharyngeal nerve (IX), and the common and interior carotid arteries.The fourth arch forms the cricothyroid muscle, the muscles of the soft palate, thyroid and epiglottic cartilage, superior parathyroids, vagus (X) and superior laryngeal nerve, subclavian artery and aortic arch (the 4th left and right aortic arches).The fifth arch does not form any significant structures in the human - it joins with the fourth arch and forms the part of the thyroid that creates C-cells.The sixth arch forms all intrinsic muscles of the larynx aside from the cricothyroid, the cricoid and arytenoid cartilage, vagus nerve (X) [with fourth arch] and recurrent laryngeal nerve, pulmonary artery and ductus arteriosus (the 6th right and left aortic arches.)By the beginning of the second month of pregnancy, the arches no longer look like every other vertebrate out there, and the embryo is now called a fetus. Though it will still be several more months before the fetus looks distinctly human and a layperson could tell the difference between it and a great ape fetus, the pharyngeal arches have set off to form the structures that allow us to survive as a species.Images:Die Wunder Um Uns. Artur Furst, 1911.American Textbook of Obstetrics. Edited by Richard C. Norris, 1895. -- source link

#evolution#jaw#pharynx#branchial arch#pharyngeal arch#bones#head#hyoid bone#trachea#anatomy#1910s#1911#artur furst#vertebrate#primordial#primordium#embryology#gills#links