Earliest Roman Restaurant Found in France: Night Life Featured Heavy DrinkingTavern more than 2,100

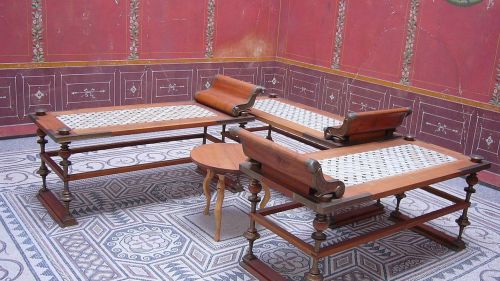

Earliest Roman Restaurant Found in France: Night Life Featured Heavy DrinkingTavern more than 2,100 years old featured same taboon oven used in Middle East today, and evidence of a Romanization process similar to what happened in ancient Israel. An ancient tavern believed to be more then 2,100 years old has been found in the town of Lattes, southern France, making it the oldest Roman restaurant found in the Mediterranean. They also found evidence that while Romanization changed the locals’ dining habits, it didn’t do much for the cuisine.Evidently some things never change, though. The excavators in the town of Lattes found indoor gristmills and ovens for baking pita, each about one meter across. This oven, called a tabouna or taboon, is still used throughout the Middle East and Israel. In another room, across the courtyard from the taboon, benches had been placed against the walls and a charcoal-burning hearth in the floor, suggesting that the dining hall was a sit-in restaurant, not a place for take-out.“Public taverns and dining halls were the locus of socializing among the various social classes of Roman society, and were also an important means for laborers and artisans to obtain a quick and easy daily meal,” says Prof. Benjamin Luley, head of the excavations and the Gettysburg College anthropology department.Roman trash adds meat to the bone The floors of the diner were covered in debris from broken ceramics. This pottery was garbage to the Romans, but a gold mine for the excavators, yielding new understanding about how the Romans feasted in the Celtic town of Lattara.Much alcohol seems to have been involved. Remains of large platters and bowls for cooking, eating and serving were found. However, the type of ware found in the largest quantity was drinking bowls.“The presence of organized drinking was shown not only by the amphorae, but also by imported drinking vessels found in large number,” explains Steve Dyson of Buffalo University. These fancy black-colored drinking bowls were imported from Italy. The Romans knew how to throw a party, and it apparently included a lot of drinking. “However, given the amount of food that was being prepared in the adjacent room (including flatbread, and cuts of meat and fish - based upon the large number of animal and fish bones), they weren’t just drinking, but appear to be eating large quantities of food,” Luley adds. The diner is believed to have served merchants and laborers who didn’t have the time or “leisure” to grow their own food, or did not have farming equipment. So they started to eat out.“In the larger cities of the Empire, some of domestic spaces in the insulae for lower classes were quite small, and sometimes lacked kitchens, which underscores the need to go to a tavern or dining hall to eat on a regular basis,” Luley told Haaretz.Dining out came with the Romans The Celts in Lattara are believed to have been farmers before the Romans marched in. However, under Roman rule, the local economy changed and new kinds of jobs developed.“Merchants looked for opportunity and moved in, often under the protection of Roman officials,” says Dyson, an expert in Roman history.In the first century BCE, roughly when this eatery existed, Mediterranean France was developing a partially monetized economy, in which more and more daily material goods could be exchanged through the medium of coins. Evidence of economic specialization begins around 100 BCE onwards, says Luley. “People were no longer focusing strictly on producing agricultural produce, especially cereal grains, for subsistence and trade with local merchants,” he says: they began to expand to more specialized commodities, some of which were exported outside Mediterranean France. The commodities produced in Lattar included wine and wine amphorae, communal wheel-thrown pottery, and farther north (especially at La Graufesenque), Gallic fine ware known as terra sigillata. A fineware Roman red-gloss terra sigillata bowl, with elaborate relief decoration,Haselburg-Muller, Wikimedia CommonsBrisk ancient trade in Languedoc wines An especially profitable business for the merchants in Lattara seems to have been wine exports. While some of the wine would have been consumed locally, much went north to be exchanged for slaves, says Dyson.Lattara is situated in the Languedoc-Roussillon region, today the world’s largest wine district and famed for its quality wine since antiquity. Based on archaeological evidence of ancient vineyards to the west of the town, the people of Lattara began producing wine on a large scale starting around 200 BCE. Mass-production of Gallic-style amphorae, to export the wine, started around 100 BCE, says Luley. Further evidence of a burgeoning economy is the increase in the number of villae in the region starting around 125-100 BCE. Many of these villae were probably cultivating grapes for wine production on a large scale as well.And with all due respect to the Romans introducing le night life, international trade in wine precedes them – the ancient Greeks were in the market centuries before the Romans came on the scene.Emulating the Romans on Passover The Celtic town of Lattara provide clues about Roman society - and also insights about how people in the provinces became Romanized.“We do have interesting evidence of new changes in dining at Lattara, which seem to reflect more influence of Roman dining practices,” says Luley.One is the existence of triclinium – a couch big enough to accommodate three, on which Romans typically dined while reclining. In addition, the presence of the terra sigillata clayware in the late first century BCE suggests new practices, namely a new “fussy” emphasis on very small plates, cups, and goblets. Those would be ideal for diners who are reclining and drinking with one hand while taking food from small plates with the other hand, explain the archaeologists. A similar assimilation of Roman customs occurred in Judaea during Roman rule. “The finds are interesting mainly for the a glimpse into the interaction process between the local Celtic population and the Romans,” says Guy Stiebel of Tel Aviv University. “The study of the material culture allows us to illustrate the process of cultural changes. One very important test case is food consumption, that is, not only what you eat and drink, but where and how you do it. In a somewhat similar manner to what we see in the French site, Judaism adopted Greco-Roman customs and incorporated it in religious traditions such as Pesach. Reclining together, eating and drinking followed the symposia,” Stiebel says to Haaretz. Even the custom of eating in a reclining position, resting the left arm on a couch and leaving the right hand free to dip and taste, is a heritage of the Greco-Roman world, many believe. But did feasting on roast peacocks and larks’ tongue pie migrate from Rome outwards too? Evidently not. “I should point out that interestingly, cooking practices don’t seem to change too much at Lattara after the Roman conquest,” Luley concludes.http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/archaeology/.premium-1.704937 -- source link

Tumblr Blog : mythologer.tumblr.com

#roman life