Taking up space: The Lady Members’ Room.Rachel Reeves MP for LeedsWest is one an incredible line up

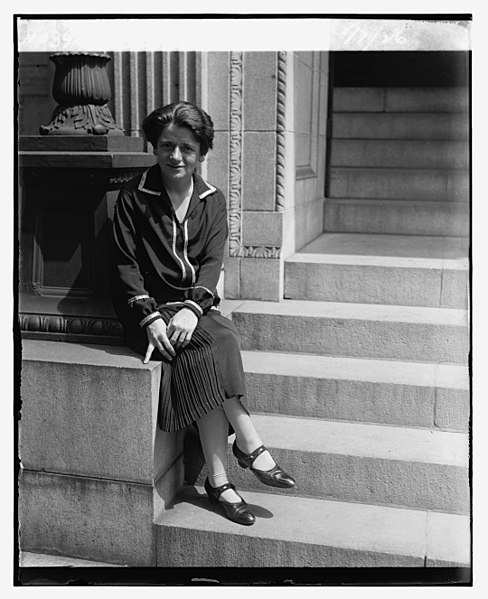

Taking up space: The Lady Members’ Room.Rachel Reeves MP for LeedsWest is one an incredible line up of people participating in our Womenand Leadership: A Symposium on 17 May that also includes Dr FarahKarim-Cooper (Shakespeare’s Globe), Claire Van Kampen, Morgan Lloyd Malcom,Professor Liz Shafer (Royal Holloway), Dr Sumi Madhok (LSE), Winsome Pinnock, DrWill Tosh (Shakespeare’s Globe), Baroness Kingsmill CBE, Rachel Reeves, StellaKanu and Gillian Woods (Birkbeck). They will discuss women in history, theirown experiences in leadership roles, the pay gap, ‘likeability’ and what kindof leadership do women or ‘should’ women cultivate?This blog is an extract from Rachel Reeves’ book Women of Westminster inwhich she gives insight into the Lady Members’ Roomin the 1920s. ‘I find a woman’s intrusion into the House of Commonsas embarrassing as if she burst into my bathroom when I had nothing to defendmyself, not even a sponge,’ Winston Churchill famously quipped to Lady Astor.She rebuffed him with a wry smile: ‘You are not handsome enough to have worriesof that kind.’ Yet Churchill’s attitude was typical of male views towards womenin Parliament.Westminsterwas, and remains today, a male-dominated institution. Charles Barry, whodesigned the Houses of Parliament, had designed a number of male-only privatemembers clubs; in many ways Parliament was just another club with a debatingchamber appended to it. The physical barriers to women’s acceptance withinParliament were particularly pronounced in those early years of women’srepresentation. The scarcity of the new women MPs, combined with institutionalsexism, meant that they were often made to feel unwelcome in the Commons. Therewere numerous cases of women MPs being mistaken for secretaries, as well asgenerally being treated with distrust and a continued sense of disbelief attheir very existence.56‘The dungeon’ The LadyMembers’ Room, a designated room where women MPs could respond tocorrespondence and dress themselves, served as an office for all women MPs.Known as ‘the dungeon’, it was a small, stuffy room in the basement of thePalace of Westminster. Mark Collins, Parliament’s estates archivist andhistorian, described it as ‘a dark place with wooden panelling.’57 WhenWilkinson first entered the House in 1924, the nearest ladies’ toilet to thedebating chamber was a quarter of a mile walk, along three long corridors andtwo flights of stairs.58 In 1929, the Lady Members’ Room was moved down thecorridor to accommodate the larger pool of women, but it was still small andlacked a changing room or an annunciator to alert MPs as to what was happeningin the debating chamber. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the facilities wereimproved. Meanwhile,male MPs had a much greater purchase on the space of Westminster. Unlike women,male members had access to baths (particularly useful during all-nightsittings) and dining rooms. Ministers (almost exclusively male) had their ownoffices, and not even Nancy Astor dared to enter the smoking room, ‘where awhispered word may sometimes have more effect than an hour’s speech thunderedin the debating chamber’, as Ellen Wilkinson described it.59 The physicalinfrastructure both facilitated, and was facilitated by, elite social networks.In almost a physical extension of the parliamentary estate, male members wouldgo to their private male-only clubs (including the Athenaeum, the NationalLiberal Club, the Garrick and the Carlton) to discuss politics.‘I am not a lady – I am a Member of Parliament’EllenWilkinson was the first woman MP to enter the smoking room. As she bounded upto the door, she was stopped by a policeman who informed her that ladies didnot usually enter. ‘I am not a lady – I am a Member of Parliament,’ sheresponded peremptorily as she opened the door. Wilkinson continued to push theboundaries of Westminster convention. In 1928 she used her position on theKitchen Committee (a select committee dedicated to the domestic arrangements ofthe House of Commons) to initiate a campaign for women to be admitted to theStrangers’ Dining Room. As it stood, while male parliamentary secretaries ofministers and opposition leaders could eat in this cheaper dining room, womenhad to eat in the more expensive Harcourt Room. Despite opposition toWilkinson’s campaign from others on the committee, including her only otherfemale colleague (Mabel Philipson), the motion passed. The speaker decided thata lady guest could be admitted for dinner, but not for lunch, on the dubiousgrounds that there was a shortage of accommodation. Astor intervened, saying:‘Do not women need luncheon, too?’ Nevertheless, this was primarily a moment ofcelebration and Wilkinson entertained a party of female guests in theStrangers’ Dining Room (a meal which was, interestingly and unusually for thetime, a vegetarian and non-alcoholic affair). But she continued to pushforwards, and when appointed to the committee once more in 1930, she was activein the campaign to admit women for lunch as well. In October 1931, Labour MPEdith Picton-Turbervill made a request for a women’s dressing-room, which wasgranted in the next Parliament. Women were beginning to ‘take up space’.Women and Leadership: A Symposium takes place at Shakespeare’s Globe on 17 May.Image: Ellen Wilkinson MP in 1926. Source:Library of Congress. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : shakespearesglobeblog.tumblr.com

#parliament#politics