unhistorical:February 19, 1942: Franklin D. Roosevelt issues Executive Order 9066. The order provide

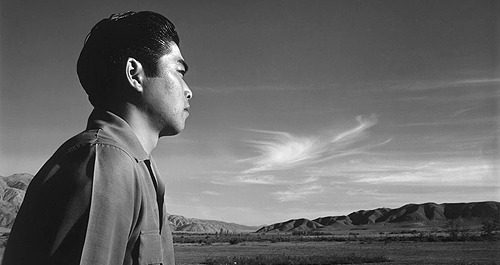

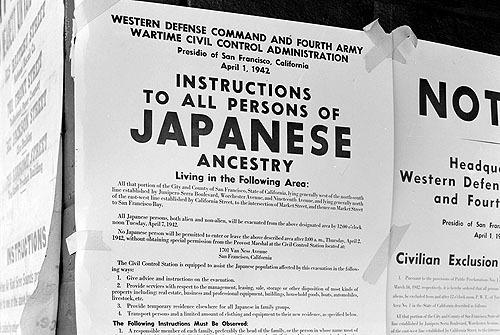

unhistorical:February 19, 1942: Franklin D. Roosevelt issues Executive Order 9066. The order provided for the designation of military areas (to be decided by the Secretary of War and commanders of the U.S. armed forces) from which “any or all persons” could be relocated. No specific ethnic groups or sections of the nation were singled out in the text of the order, but it stated that these new powers would serve as “protection against espionage and against sabotage”. In practice, it resulted in the internment of 120,000 Japanese-Americans, nearly two-thirds of whom were American-born citizens; smaller numbers of German- and Italian-Americans were interned as well, but no ethnic group was targeted by the government to the extent that the Japanese were. Virtually every Japanese-American living on the West Coast was interned, while a small fraction of those living in Hawaii - just over a thousand - suffered the same fate. The justification for the executive order was practical; it was believed that many Japanese, Issei and Sansei alike, could not possibly remain loyal to the United States if it went to war with Japan. It was outwardly practical (the Ni’ihau Incident seemed to prove American suspicions), and it was deeply rooted in racial prejudice. Many white farmers were glad to see their Japanese competition uprooted and displaced; several newspapers printed opinion pieces that supported wholeheartedly the internment based on their own personal feelings toward the Japanese; the American public (including even Theodore Geisel/Dr. Seuss) generally supported the move; and the Supreme Court, the ultimate defender and interpreter of the U.S. Constitution, upheld the constitutionality of the executive order in Korematsu v. U.S. (also see: Hirabayashi v. U.S.). Camps were run by the Wartime Civil Control Administration and the War Relocation Authority; the largest of these by population were Tule Lake and Poston, but the most well-known today is Manzanar. Some Japanese-Americans escaped internment by volunteering to serve in the U.S. Army, and many of them served in the famous 442nd Infantry Regiment, a unit that fought in Europe after 1944. Ironically, while many of its members’ families remained interned at home based on widespread racism and suspicions of disloyalty, this all-Japanese unit eventually became the most decorated infantry regiment in the history of the U.S. Army: twenty-one of its members were awarded the Medal of Honor. Executive Order 9066 was eventually rescinded in 1976, and surviving Japanese internees received payments and apologies from the U.S. government in the 1990s. But money paid four decades later could not compensate for the time lost in the camps; the businesses, homes, farms, and other property sold last-minute at ridiculously low prices by their owners or vandalized and destroyed in their absence; and the humiliation and disillusionment at having been denounced by their own countrymen and rounded up by their own government. Images compiled by The Atlantic -- source link

Tumblr Blog : unhistorical.tumblr.com