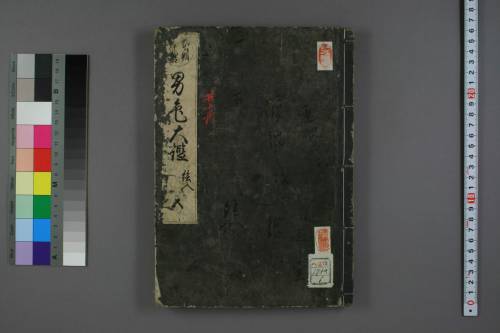

gaymanga:The Great Mirror of Male Love (男色大鑑 Nanshoku Okagami), 1687 Collection of stories by Ihara

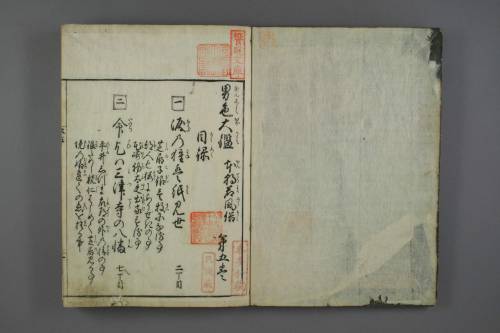

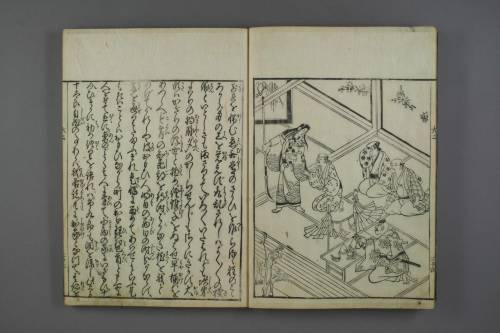

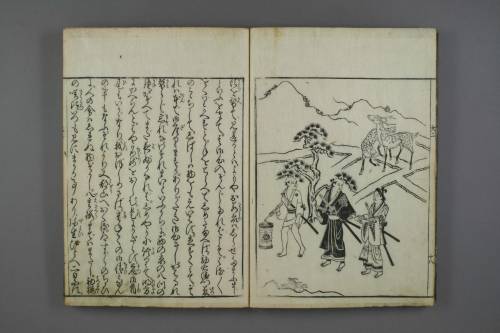

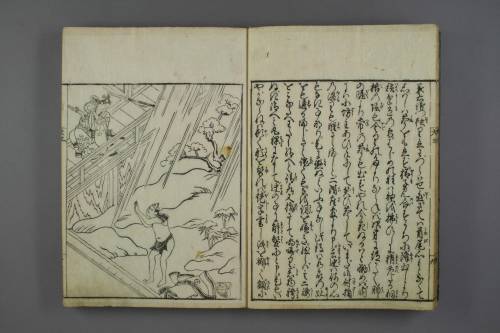

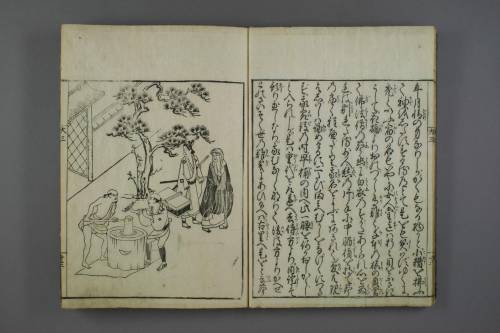

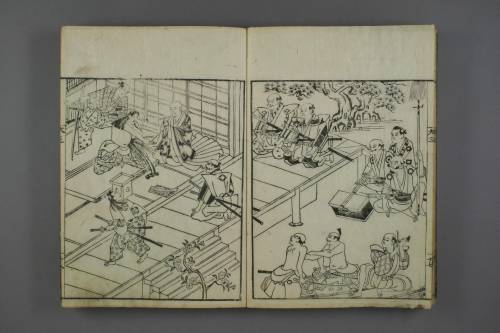

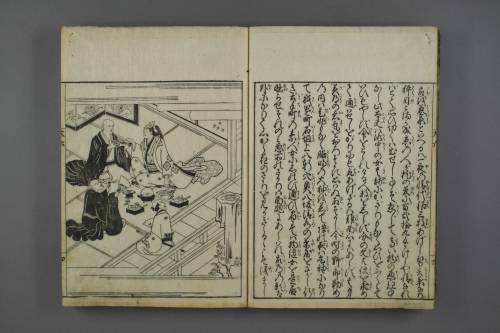

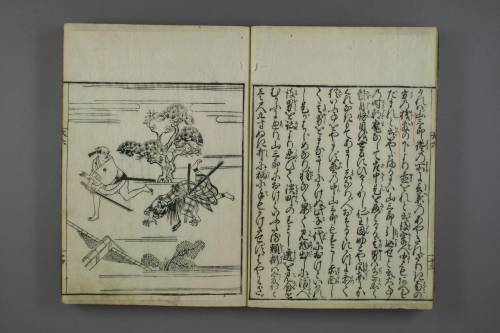

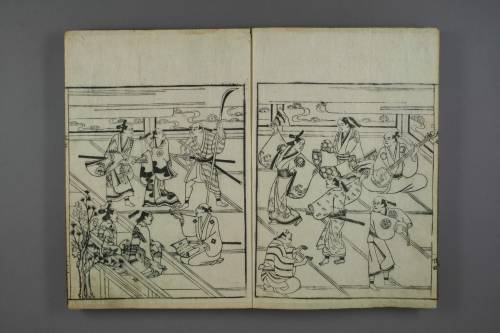

gaymanga:The Great Mirror of Male Love (男色大鑑 Nanshoku Okagami), 1687 Collection of stories by Ihara Saikaku (井原西鶴)Photos via the Waseda University Library CatalogJapan’s been portraying male-male sexuality in popular culture for centuries. The Great Mirror of Male Love was a bestseller in 1687! This collection of short stories by the renowned poet Saikaku was not an anomaly, either— just part of what Gregory M. Pflugfelder describes as “a lively and increasingly commercialized culture” in 17th century Edo that “articulated itself through such prose texts as Saikaku’s, but also in poetry, song, dance, drama, woodblock prints, and, of course, the various pleasures of the flesh.”The titular “male love” referred to by nanshoku (男色, lit. “male colors”) cannot be equated with modern conceptions of “homosexuality,” because in the Edo period, as Mark McLelland describes:[…] There was no necessary connection made between gender and sexual preference, because men, samurai in particular, were able to engage in both same- and opposite-sex affairs. Same-sex relationships were governed by a code of ethics described as nanshoku (male eroticism) or shudo (the way of youths) in the context of which elite men were able to pursue boys and young men who had not yet undergone their coming-of-age ceremonies, as well as transgender males of all ages from the lower classes who worked as actors and prostitutes.More on Nanshoku Okagami, from Paul Gordon Schalow’s introduction to his English-language translation, The Great Mirror of Male Love:A feature of premodern Japanese culture was that male homosexual relations were required to be between a man and a boy, called a wakashu. When a wakashu reached the age of nineteen, he underwent a coming-of-age ceremony that conferred on him the status of an adult male, after which he took the adult role in relations with boys. The first twenty stories in Nanshoku Okagami highlight wakashu from the samurai (warrior) class whose lives exemplified the ideal of boy love; the second group of twenty stories shifts its focus to kabuki actors, who exemplified boy love in their own way, serving as boy prostitutes in the theater districts of Japan’s three major cities, Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo (Now Tokyo).Books on sexual love, such as Nanshoku Okagami, flourished in the seventeenth century in response to a demand from Japan’s emergent urban class of merchants and artisans, called chonin (townsmen). These books reflected the cultural assumption that romantic love was to be found not in the institution of marriage, but in the realm of prostitution. Recreational sex with both female and young male prostitutes was a townsman’s prerogative if he could afford their fees, and he chose between them without stigma. A cult of sexual connoisseurship grew up around them each: nyodo, “the way of loving women”; and wakashudo (abbreviated to shudo or jakudo), “the way of loving youths.”I’ve been enjoying reading Saikaku’s highly imaginative fables (via Schalow’s translation) and sometime soon I’ll post some excerpts from the tales here along with the fantastic woodblock prints that accompany them (as seen above). -- source link

Tumblr Blog : gaymanga.tumblr.com