In ancient Egypt, what we call medicine was understood as a form of magic. Practicing medicinal magi

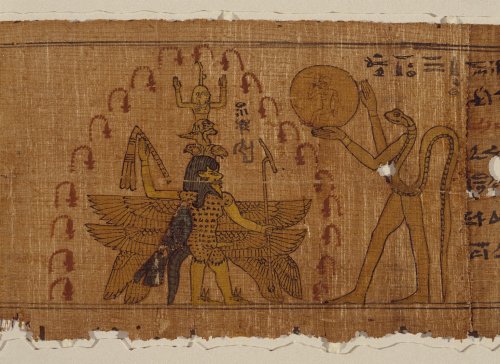

In ancient Egypt, what we call medicine was understood as a form of magic. Practicing medicinal magic honored the goddess Sakhmet, the ferocious, lion-headed protector of Egypt. Though she is often thought of as protecting Egypt from invasion, this life-size sculpture of the goddess was one of hundreds commissioned by king Amunhotep III for his funerary complex, which scholars believe were meant to thank the goddess for the ending of a plague that ravaged the region. Sakhmet was believed to be so ferocious that if her wrath was not calmed after the enemy was defeated, she may bring about the end of the world. She could be placated with offerings of beer dyed red to resemble blood as well as the flooded Nile carrying silt, suggesting renewal and rebirth.Like today, preventing disease was the first course of action. The ancient Egyptians turned to apotropaic deities who were believed to be able to scare-off the evil and chaotic forces, including those that caused disease. A magical knife, adorned with the head of a protective leopard, and fearsome, hybrid gods—lion-headed Aha showing domination over poisonous snakes, and hippo-based Tawaret wielding a knife herself—would cut the heads off of demons. Over time, gods like Aha, and the similar Bes, were ascribed more and more traits to address more and more concerns. This seven-headed figure with four sets of wings, the tail of a falcon and a crocodile, the heads of jackals for feet, and enveloped in a ring of fire is an example of a deity so mysterious and powerful that it could guard against a variety of maladies described on this small papyrus scroll meant to be rolled up and carried around.In the final weeks of 2020, we’re taking time to find comfort, hope, and healing with artworks in the Museum’s collection. Egyptian, Bust of the Goddess Sakhmet, ca. 1390-1352 B.C.E. Granodiorite. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. W. Benson Harer, Jr. in honor of Richard Fazzini and the excavations of the Temple of Mut in South Karnak, Mary Smith Dorward Fund and Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 1991.311. → Egyptian, Fragment of “Magic Knife,” ca. 1759-after 1630 B.C.E. Frit. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield, Theodora Wilbour, and Victor Wilbour honoring the wishes of their mother, Charlotte Beebe Wilbour, as a memorial to their father, Charles Edwin Wilbour, 16.580.145. → Egyptian, Scene from a Magical Papyrus, 664-525 B.C.E. Papyrus, ink. Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Theodora Wilbour from the collection of her father, Charles Edwin Wilbour, 47.218.156a-d. -- source link

#reflectionsonhealing#bkmegyptianart#egyptian art#egyptian#sakhmet#healing#magic#medicin#goddess#lion#protector#plague#renewel#rebirth#disease#prevention