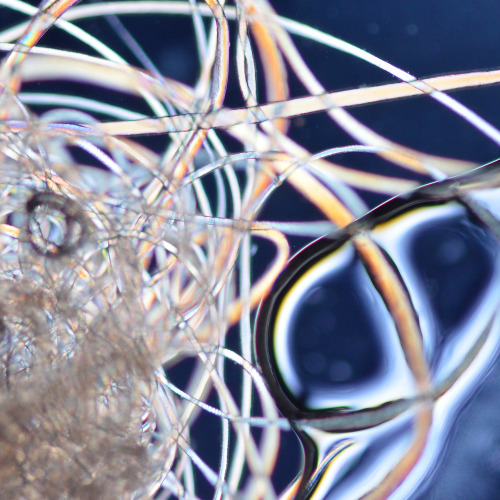

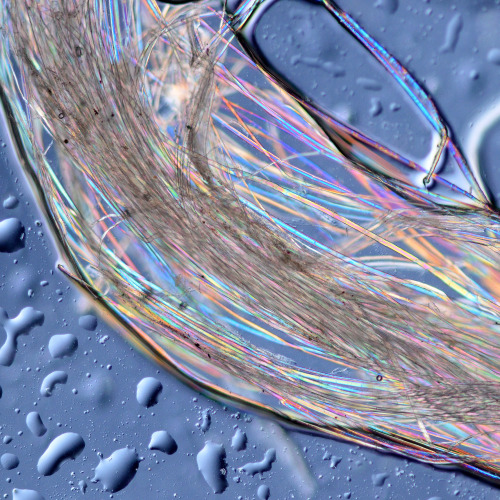

FORMLESSNESS by Sarah CraskeI have been reminded of a favourite artwork of mine called Untitled (Tat

FORMLESSNESS by Sarah CraskeI have been reminded of a favourite artwork of mine called Untitled (Tate), by Fischli and Weiss. It was an installation commissioned in 2000 for the opening of Tate Modern.On entering the room you are presented with a gallery space under construction, incomplete, clearly being decorated in preparation to display further works. There are all the usual tools associated with a gallery re-hang present, and some unusual objects too, which may or may not be part of the artwork about to be installed. Essentially it’s a working space. Pallets, masking tape, pots of paint, brushes, trays, tape measures, levels, pens, cups of coffee, tool boxes: you name it, it’s all there. On first encounter you look at all of the objects in the room, and you’re not quite sure whether it’s an artwork, an installation, or genuinely part of the re-hang. At this stage many people, and I mean many people, leave the room. It is the general assumption that either this part of the gallery is not open to the public whilst in a state of transition, or that it’s another ‘pile of bricks’. Few people actually look. I had a wonderful experience on my first encounter with this work. I did not know anything about it beforehand, and what happened next was an experience that I will never forget.I looked, like I always do, just in case … just in case I observe something.In this instance, it was a cotton bud. A fairly insignificant item on a table made out of plinths and wallboard. It was nestled between other objects, that were all clearly in use and part of the working ephemera made manifest. But there was something about it: it just didn’t ‘look right’. I recognised the surface texture as being of some other materiality than that of a cotton bud. The plastic shaft wasn’t shiny enough, whilst the buds weren’t soft enough. Because of its uncanny nature, I looked closer, and realised it wasn’t a cotton bud at all, but a small sculpture of a cotton bud. As soon as I read this object correctly, the whole artwork unravelled[1] slowly before my eyes. Every item in front of me had been painstakingly hand carved out of polyurethane foam and then painted, with such exquisite attention to detail that even the coffee had bubbles in it. Everything before my eyes was a photorealist sculpture, beautifully executed and referential[2].It was this moment of visual unravelling and understanding that I was reminded of when receiving my Value blog from Charlotte, who had kindly read and edited it for me.I always enjoy getting feedback from Charlotte. I really value her thoughts and reflections on my thinking, especially from a different perspective. I also enjoy our relationship. I am an artist and she is an academic. This framework gives us a sense of critical freedom that we wouldn’t necessarily enjoy if we were working in the same field. It is fun and playful, whilst at its core incredibly serious.As usual my document was littered with various grammatical revisions. Charlotte is much better at grammar than I, and I delight in her attention to detail and obsessive behaviour as these similarly manifest themselves (albeit in other forms) for myself. In some instances however, I might ignore her more automatically correct suggestions. Creative writing and text as artistic material is an area that I’m testing within this project. It is new to me within my own practice and I want to develop this area of expression. We have already accumulated a lot of data, and I have been reading W.G. Sebald as an example of how to organise thoughts and information over a period of mental and physical travel, within narrative text. His exploration of the landscape and associated ‘information’ in Rings of Saturn seems a fitting example of how I might approach recording and reflection upon our various discoveries, as we ourselves tread a microbial landscape across the book’s pages.Whilst I was appreciatively ticking through the sea of blue commentary boxes that had washed across my text, I stumbled over a revision of a word that had caught me entirely off guard. Charlotte had changed ‘the object to ‘any object’. Now those of you reading as fine artists will immediately spot the immense difference between these two combinations, the initial referring to the canon that is object theory and the latter being nothing other than the literal use of the word. I couldn’t accept this revision and thought perhaps it had been a mistake. I wasn’t going to have Charlotte in three keyboard taps wipe out an entire framework of thinking within my discipline - thank you very much. I carried on. What appeared soon after was a puzzling question in the comments box. I had referred to the fact that the question of value had returned to me, and this question had immediately followed my nod to object theory, politics, artistic content (as in Ovid’s stories themselves) and other metaphors that I was ascribing to the book. These reawakened thoughts and associations clearly had a relationship to how I valued the object and I therefore felt a little bit more puzzled. I carried on.I then let out a gasp. Charlotte had replaced ‘showcased’ with ‘glamorous’. Not only had she denied me my shelf of object theory literature, she had then overburdened my paragraph with ‘glamour’. This is a word that I would absolutely not use, unless very, very specifically. As an artist that strives for truth and the real through expression, the idea of even referring to glamour seemed incongruous, and in the context of house clearance stores wanting to sell their wares, why would they display objects in a deceitful way? I had felt like she had dumped a huge pile of books in the middle of my paragraph (fashion theory, photography theory, etymology, semiotics and philosophy) and I had no idea what to do with them.The edit that unravelled this whole process for me however was Charlotte’s challenge of the word ‘formless’ that I had applied to the book. Now formlessness, or the ‘informe’, is one of my areas of subject interest, and I had used this word most purposefully. The notable work Formless: A User’s Guide by Kraus and Bois is a wonderful survey of artworks that discuss the notion of formlessness within the avant garde and modernism, challenging the binary relationship between form and content[3]. Thinking about our copy of Metamorphoses in terms of its entropic state, decay and transient nature, fits very nicely within Kraus and Bois’ framework of ideas. I would even go so far as to say that the stories themselves held within its pages of metamorphoses are never fixed in their form. But it was at this point I noticed the pattern.Charlotte had revised throughout my blog all the words that related most directly to my discipline. I then, and only then got a glimmer of another possibility. It was at this point that I realised that we may have had very different interpretations of my writing. Charlotte could have read it from a purely narrative perspective where as I had laid the narrative over a framework of art theory to communicate to the fine art audience which areas of thinking I was using for my research pathway in this project.[4]If this was true, we had a problem. This meant that all my references could be missed and misinterpreted. This also meant that I could equally be missing the same type of content when reading Charlotte’s and Simon’s blogs. And given that we were all genuinely trying to work from the same page, but then reading that page differently, I was at a loss as to how to proceed.I again reflected on Fischli and Weiss’ uncanny work…and yes, that’s the uncanny, not the uncanny.[5]“Perhaps our carved objects have more of an affinity with painted still lifes. In the case of Duchamp the concept of objets trouvés, or ‘found objects’, is important, whereas we try to create objects. Duchamp’s objects could revert back to everyday life at any point in time. Our objects can’t do that, they’re only there to be contemplated. They’re all objects from the world of utility and function[6], but they’ve become utterly useless. You can’t sit on the chairs we carve. They are, to put it simply, freed from the slavery of their utility. Nothing else is left other than to look at this chair. What else can you do with it?”(Fischli in Fleck, Söntgen and Danto 2005, p.22.)[1] CS: Another moment where I don’t understand formlessness. I would say ‘unfolded’ – isn’t unravelling a bad thing?SC: I looked up this word in the Oxford Dictionary to see if I had used the word correctly within its terms, as well as my own. The three interpretations of unravel are: 1. To cause to be no longer raveled, tangled, or intertwined, to disentangle; to unweave or undo (a fabric, esp. a knitted one). Freq. in figurative context.2. To become undone, disentangled, or unraveled. Freq. fig. or in extended use.3. To reverse, to undo; to annul4. To make plain, disclose, reveal; to investigate and solve (a mystery, etc.), to work out. Also refl.This is exactly what I meant. The illusion that had been successfully created by the artists began to collapse as I started to be able to read the physical reality of what was in front of me. As my visual understanding increased, the illusion diminished. The truth appeared through purposeful use of visual codes that were meant to defy and confuse the audiences visual experience. The work is making the point that what we may believe to visually understand, is only reliant on our own ‘Ways of Seeing’, interpreting and the visual codes we carry with us. Our understanding of the visual world, may by no means be true (setting aside for now the issues with ‘truth’).[2] CS: Huh? To what?SC: Really? Right. Erm…This work references many dialogues that have occurred within the study and creation of art that I suppose as a cultural practitioner I instantly recognise. These dialogues are revisted and reinterpreted through the discipline, with the intent of pushing ideas further. So from still life to trompe-l’oeil painting, illusion and reality, object theory, Duchamp’s readymade & semiotics to name a few. Common languages that I suppose we read when experiencing art.[3] CS: Please expand and explain formlessness some more. There’s not enough here for me to get it (or begin to, I should say)SC: I think what has made itself apparent is perhaps a need to discuss what I understand to be the relationship the object has with form and function? This will then make formlessness much clearer, as it is a concept that attempts to challenge the form/function dialogue. [4] CS: Yes, you are spot on here I think. I always have an instinct to turn things into the best possible story (most generalist, most dramatic) for the widest possible audience. It’s all about making a narrative for me. How unfair that you (and Simon) have to play on my turf. Suppose we had to communicate by artworks. Then I would be stuffed.SC: This is another example of reality unravelling before me. As soon as I had the smallest notion that you may not be recognising my referencing, the pattern of faux amis throughout the text ‘unravelled’ and became apparent. This is interesting. Who is our blog audience? I had assumed that though informal in nature, I was pitching to the ‘art world’, where as both you and Simon would be communicating to your communities? Given our subject matter, I’m afraid I need some help in understanding why we would communicate to the widest possible audience? What does that serve? And are you not patronising that audience by assuming that they want ‘general and dramatic’? This is a very different approach to ‘the audience’ to one I would employ as an artist. Surely by regulating our language between the disciplines, we are by the very nature of that process making our ideas more accessible? And finally, what do you mean that we are playing on your turf? Are you saying that History communicates in this way? And I don’t know if you have noticed, but I have started to communicate with artworks. This was one of my intentions, as it would demonstrate the breadth of artistic practice and would provide in roads into the various disciplines and academic thinking within the discipline. Is this something that you would prefer me not to do? I thought it would be helpful as a way of encouraging both you and Simon to think about the art we will be creating in a more of an engaged, rather than superficial way.[5] CS: Huh? Aren’t these the same??SC: No. I was attempting humour, but obviously it didn’t translate. I was implying that one would read the word ‘uncanny’ from a dictionary definition point of view:“strange and mysterious, especially in an unsettling way’.Where as I meant Freud’s development of the term ‘Uncanny’ which is something that is taught in art college, as it explores that feeling experienced when you come into contact with both the familiar, yet unfamiliar. So it is a specific psychoanalytical term that is regularly referenced and striven for in artwork by many artists.[6] Here’s an example of puzzle for me: to me form is the counterpart to function (something I get from my early education in biology). This sounds to me like it eschews function, not form. Clearly I am thinking with different categories to you. Can you explain?SC: I suggest that we write a blog about this to explore this further, as I suspect Simon will also have a take on the form/function relationship? I also have no idea how these words relate to biology and science! Artwork Credit: Sarah Craske, ”Thread Nebula”, 2015. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : metamorphosesinartandscience.tumblr.com

#sciart#artscience#science#microscopy#sarah craske#simon park#charlotte sleigh#metamorphoses#formlessness#informe#tate modern#untitled#carl andre#installation#uncanny#object theory#gallery#scultpture#sebald#readymade