Why February 12th is BRILLIANTConflictToday we are rather torn. We have a saint who we first discove

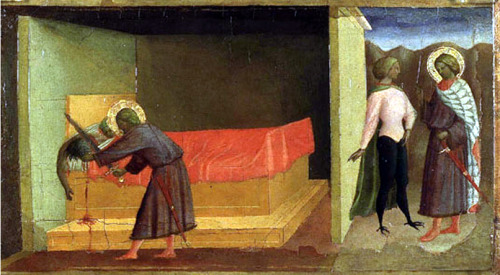

Why February 12th is BRILLIANTConflictToday we are rather torn. We have a saint who we first discovered a year ago, when this blog was no more than a series of text messages sent during the Leicester Comedy Festival. We also have one of a triumvirate of very peculiar Dutch anatomists whose work we have come to enjoy over the last six months or so. We may have to tell you about both.Today is the feast day of Saint Julian the Hospitaller. We’ve no idea when or where he lived, but he is easily our favourite in our category of unlikely saints. When we’re looking at saints, generally what we’re most interested in is how they are depicted in art and what they have been declared ‘patron saint’ of. A quick scroll through the information on Saint Julian revealed that he is sometimes pictured as: 'man listening to a talking stag’ or: 'young man killing his parents in bed’. Among other things, he is the patron saint of innkeepers, carnival workers and murders.The story of Julian is not unlike that of Oedipus but without the 'sex with his mother’ part. At the age of ten, Julian left his parents home. Perhaps because he had been cursed by witches who foretold that he would one day kill his own parents. There is another story which tells us that he was completely obsessed by hunting and that, while out in the forest, he shot a talking stag which told him that because Julian had shot him, when he wasn’t doing any harm but just having a bit of a rest in the undergrowth, he would one day kill both his parents and that there was nothing he could do to escape his fate.But Julian did try to escape, he ran away hoping never to see his parents again. He eluded his fate for twenty years. He settled down and got married. But when he was thirty his parents, who were searching for him arrived in the town where he lived. In a freak encounter, they met his wife who immediately invited them back to the house. Julian was, at the time, out hunting and she suggested his parents, who were tired after their journey, had a bit of a lie down while they were waiting. Meanwhile Julian was visited by a shadowy figure, who we presume to be the Devil, but he is referred to as 'the enemy’. You can see the enemy pictured above, he’s the one in the pink leotard. The enemy told him that his wife was at home in bed with her lover. Julian rushed home, saw two figures sleeping in his bed and immediately killed them both. Then, his life once more in ruins, he was about to leave town when who should he see but his wife. She told him the story and they both realised what had happened. Of course, they both felt terrible about it and Julian and his wife moved away. They took up ferrying people backwards and forwards across a river and taking in weary travellers as penance. Then one day they ferried a leper over the river in a terrible storm. They warmed him, fed him and even acquiesced when the leper asked to be put to bed with Julian’s wife when he just couldn’t get warm. Luckily, the leper turned out to be an angel in disguise and he forgave them for their sins. All this is in an extremely long and dull account of the Saint’s life from the Golden Legend. Take our advice and give it a miss. But it seems to end with Julian and his wife being murdered in their beds by robbers.If you want to read something really spectacular about Julian the Hospitaller, there is a story by Gustave Flaubert. In it, Julian is an enormously blood-thirsty child whose trail of slaughter begins with him killing a mouse in church and escalates until he slaughters an entire valley full of deer. That’s when he gets cursed by the stag. At the end, the leper gets into bed with Julian, not his wife. You can find it here. Or, if you don’t like the sound of that, there is a tale in Bocaccio’s Decameron about a devotee of Saint Julian which is relatively easy to find. The Decameron is a long series of one hundred tales that is, in format, a little like the Canterbury Tales. It is an early written source for many of the fairy tales of Perrault. In Bocacchio’s tale, a travelling merchant, who always prays to Julian for a good place to spend the night, is attacked by robbers, abandoned by his servant and left out in the snow in just his shirt. But then he gets taken in by a lady whose lover has deserted her for the evening. They both have a lovely time and it all ends happily. Today is also the birthday of Jan Swammerdam, which is an excellent name. Swammerdam was born on this day in 1637 in Amsterdam. He is probably best remembered for his work on insects. He discovered that insects do not spontaneously spring to life out of the mud, like everyone thought, but come from eggs and larvae. He discovered this using a microscope and once dissected a caterpillar for Cosimo de Medici to show him that it already had, inside its body, the beginnings of the wings it would grow when it became a butterfly. He also found, more than a hundred years before Galvani, that when the muscle of a frog’s leg contracts, it does not increase in size. He expected that it would because it was thought that muscles were controlled by animal spirits running through the nerves. If the muscle was full of spirits, it should get bigger. It didn’t. If anything, it shrank a little. Unfortunately, Swammerdam just thought there was something wrong with his experiment and he abandoned it.Neither of those things are how we first met him though. We came across him because of a huge controversy between himself and fellow student Regnier de Graaf over who had been the first to discover that eggs grew inside human female ovaries. Both men had been students of Johannes van Horne at the university of Leiden in the Netherlands along with a man now known as Steno. Anatomists had dissected female reproductive organs before, they had noticed ovaries, but referred to them as 'female testes’ and didn’t really know what they were for. Steno theorised that they would probably turn out to contain eggs: “I have no doubt that the testicles of women are analogous to the ovary” was what he said, but he didn’t do anything to prove it. Swammerdam and his tutor van Horne did though. They set about trying to find the eggs in human ovaries. Van Horne managed to publish a brief account of his discoveries in 1668. But then in 1670, he died of plague. Swammerdam continued their work but soon found out that fellow student, de Graaf, was working on the same thing.What happened next was something between a race to publish and a fight that dragged in the newly formed Royal Society in London. De Graaf published a paper where he theorised that the eggs were fertilised by seminal vapour rising up from the womb. Swammerdam responded by drawing a picture of a dissected human ovary and uterus and sending it to the Royal Society. In March 1672 de Graaf published a book about female generative organs. He had noticed that, in rabbits there were burst follicles in the ovaries after mating and also round objects in the fallopian tubes. He concluded that they were eggs that had come form the burst follicles and that it was as a result of mating.Swammerdam published his own account two months later. He said the bursting follicles thing was nonsense because he had observed the same thing in the ovaries of virgins. He also stated that he and van Horne had come up with the idea first (there was no way of proving him wrong) and also de Graafs drawings were rubbish. Swammerdam dedicated his book to the Royal Society and also sent them a beautifully preserved female uterus along with twelve other items of genital anatomy, including a dissected penis, a clitoris and a hymen. He asked the Royal Society to adjudicate in their argument over which of them had come up with the idea of women having eggs first. De Graaf came back with a publication entitled: 'Partium Genitalium Defensio’ (Defence of the genital parts). In it he was very rude about Swammerdam and accused him of being 'blinded by anger and hatred’, but didn’t really come up with any new evidence that would help with the egg controversy.We feel rather sorry for the Royal Society. How were they supposed to come up with a suitable answer? They appointed a committee of three and eventually found in favour of… Steno. It didn’t really matter though because de Graaf died a week before they made their final decision. Swammerdam wrote a reply, but we don’t know what he said, because the letter is lost. Steno had, by that time, given up science and become a bishop. So he probably never knew about any of it. The Royal Society had had enough of it all by then and didn’t even publish the report on their findings for another eighty years. They liked Swammerdam’s anatomical specimens though. Their secretary, Henry Oldenberg described them as: “very fascinating and prepared with exceeding ingenuity.” In fact, in later years he got into trouble with the Royal Society for taking them home with him. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : whytodayisbrilliant.tumblr.com

#february 12th#whytodayisbrilliant#gustave flaubert#decameron#jan swammerdam#ovaries#royal society