Alice Constance Austin (1862–1955) was a self-taught designer, feminist, and socialist. Her un

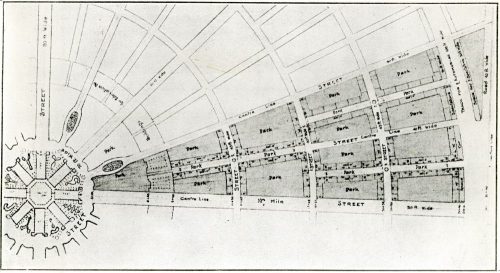

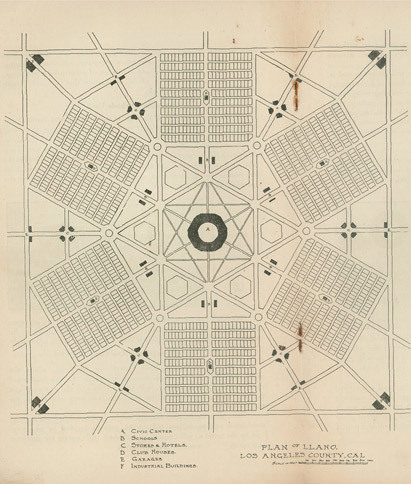

Alice Constance Austin (1862–1955) was a self-taught designer, feminist, and socialist. Her unrealized plans for the cooperative colony of Llano del Rio, California, included kitchenless houses with cooked food delivery and other innovative features intended to improve the lives of women. In 1935, she expanded upon these ideas in a pamphlet, The Next Step: How to Plan for Beauty, Comfort, and Peace with Great Savings Effected by the Reduction of WasteIn her plans for the cooperative colony of Llano del Rio, located north of Los Angeles near Palmdale, California, and in The Next Step, Austin articulated an imaginative vision of life in a socialist, feminist society.Drawing on the communitarian socialist tradition in the United States, the Garden City movement in England, and the feminist consciousness of her time, she proposed a city of kitchenless houses. She believed that dwellings without kitchens would free women from the drudgery of unpaid domestic work and that the substantial economies achieved in residential construction of this kind would permit the development of extensive public facilities, including community kitchens and kindergartens.Austin hoped to eliminate “the thankless and unending drudgery of an inconceivably stupid and inefficient system.” As the colony quickly expanded so did its infrastructure. Irrigation ditches were laid to water acres alfalfa, corn, vegetables, fruit orchards and livestock. Housing (both permanent and temporary to accommodate the large influx of new colonists) was built using materials produced at the on-site sawmill, quarry, limekilns and other industrial shops. In addition, a hotel, commissary, and dairy along with several industrial buildings including a grain silo were constructed. The soap factory, laundry, tannery, cannery, bakery, printing press, machine shop, post office, barbershop and other trades provided employment. Children were taught at one California’s first and largest Montessori schools. By 1917, there were over 900 colonists living at Llano and more than three quarters of their provisions were supplied internallyAustin’s houses were never constructed by the Llano del Rio colony. Austin, Job Harriman, and the colonists encountered many disappointments at Llano: they were tricked by a land speculator; their proposed irrigation system failed; and some of the colonists finally relocated to Louisiana, where the colony survived until 1938. Austin stayed in southern California, refined her plans, tried to patent some of her ideas, and waited until 1935 to publish them as The Next Step. She was seventy-three. By then, planning for the Greenbelt Towns was part of the New Deal, and perhaps she thought cooperative communities were viable once again.Job Harriman, a lawyer by training and a politician by proclivity, was the founder of the socialist cooperative colony known as Llano del Rio. Harriman, a former candidate for governor of the state of California on the ticket of the Socialist Labor Party and 1900 vice-presidential candidate of the Social Democratic Party on a ticket headed by Eugene V. Debs, was long an advocate of political action for the achievement of socialism in America. To become a member of the colony, one was required purchase exactly 2,000 stock shares and to reside at Llano at the par value of $1 per share.As a short-lived experiment in American socialism, Llano del Rio may have been successful – but in terms of fostering an authentically egalitarian community free of racism it had failed. states at the bottom of the call “Only Caucasians are admitted. We have had applications from Negroes, Hindus, Mongolians and Malays. The rejection of these applications are not due to race prejudice, but because it is not deemed expedient to mix the races in these communities.” Indeed, the founders may not have intentionally intended to promote racial prejudice as the advertisement suggests, but offered no opportunity for people of color to join the colony.Llano’s real death knell had come in July 1916, when the colony’s application to secure their water rights and build a dam to help irrigate their fields was denied. By fall of 1917, they had found a suitable new homestead—an old mill town in Louisiana they named New Llano. By early 1918, Llano del Rio had been involuntarily forced into bankruptcy and most of its colonists had begun to leave, some for New Llano.New Llano never attained the same size or level of productivity as the original colony. This failure was most likely due to cultural clashes with the greater culture of Louisiana and the Great Depression.Llano del Rio exists today in the form of desolate chimney stacks and a singular silo in the sands of the Mojave off the CA-138 E in Antelope Valley, just the outline of what it once was and what it once stood for over 100 years ago.https://pioneeringwomen.bwaf.org/alice-constance-austin/http://www.baremagazine.org/radical-rad-socialistfeminist-architecturehttps://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-feminist-architect-who-tried-to-liberate-kitchens-from-houseshttps://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/llano-del-rio-experiments-in-desert-utopic-livinghttps://www.kcet.org/shows/artbound/llano-del-rio-experiments-in-desert-utopic-livinghttps://la.curbed.com/2017/5/1/15465616/utopia-socialist-los-angeles-llano-del-riohttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llano_del_Riohttps://podbay.fm/podcast/596209254/e/1494268320 -- source link

Tumblr Blog : zazamatic.tumblr.com

#utopian#feminist