Subduction through the mantleA few days ago I described the “Wadati-Benioff zone” as one

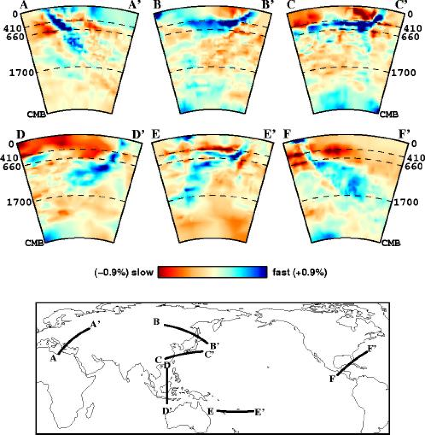

Subduction through the mantleA few days ago I described the “Wadati-Benioff zone” as one way of tracking the remnants of oceanic plates as they subduct into the Earth (http://tinyurl.com/mjcg7n7). A subducting oceanic plate is colder than the mantle around it, cold enough that it can produce earthquakes until it reaches 700 kilometers depth.Geophysicists have another tool that allows them to track subducting plates even deeper than that called seismic tomography. When an earthquake happens anywhere on Earth, it sends out seismic waves in all directions. Some of that energy passes through the entire planet and can be detected by seismometers on the opposite side of the planet.Those seismic waves travel through whatever rocks are in the mantle, and in the process they are slightly altered by the trip. Some rock types slow down seismic waves, some speed them up. From a single seismic station you can’t tell much about the mantle, but if hundreds of stations detect a single earthquake, that’s a setup where computers can help.In medical facilities today, computers are regularly used to reconstruct 3-D pictures inside the human body. To do this, data needs to be collected at a points surrounding the body, as in an MRI tube. Seismic tomography works the same way; with enough data points from hundreds of seismic stations and earthquakes, a computer can reconstruct a 3-D picture of where seismic waves slow down and where they speed up. The differences are tiny, less than 1% changes in the wave speed, but enough that modern equipment can detect it with accuracy.In addition to the composition of the rocks, the temperature of rocks also affects seismic waves; cold rocks transmit seismic energy faster. If oceanic plates are cold when they subduct, seismic tomography has the potential to track them most of the way down through the mantle, and here you see exactly that. The red and blue images are cross-section paths across subduction zones in seismic tomography. The blue blobs on their way down are cold objects in the mantle. They start at the surface at locations of subduction zones and the deepest ones reach depths of over 1700 kilometers into the mantle. Seismic tomography is precise enough to track slabs down almost the entire way through the mantle.Interestingly, one feature in many of those slabs stands out. When the slabs reach a depth of ~700 kilometers, several turn horizontal. That level is interesting as at about 660-670 kilometers deep, the main phase in the mantle changes. The upper mantle is dominated by a mixture of garnet and olivine-like minerals called Wadsleyite and Ringwoodite; at 670 kilometers depth, those minerals all change into Bridgmanite, the most abundant mineral inside the Earth. The fact that slabs appear to get hung up at this level means that there is some strength to that transition; it’s hard for things to get across. That means it is at least possible for that phase transition within the mantle to serve as a major dividing line, between partially isolated upper and lower mantle areas, over geologic time.-JBBImage credit: http://eesc.columbia.edu/courses/v1011/topic_4_2.htm -- source link

Tumblr Blog : the-earth-story.com

#subduction#science#geology#seismology#geophysics#earth#tomography#wadatibenioff zone#earthquake