doughtier:ricekrispyjoints:nerdyqueerandjewish:captainlordauditor:jewish-privilege:palominojacoby:ka

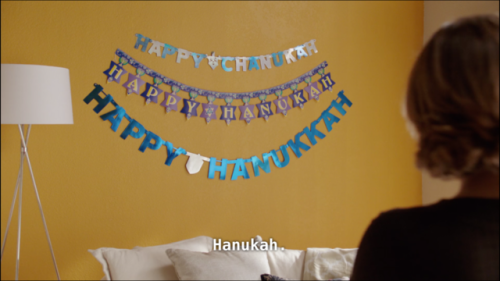

doughtier:ricekrispyjoints:nerdyqueerandjewish:captainlordauditor:jewish-privilege:palominojacoby:kazoobard:Jewish moodIt’s almost that time of the year!?חנוכה?חֲנֻכָּהXanike?xanike made me ascend out of the physical realm and into an astral planeHonka and Xanike are on opposite sides of the spelling spectrum the answer to “how do you spell Hanukkah” is “with a different alphabet”Gather round, my children, and let me tell you how to spell this pesky word.I’ll start by what everybody agrees on in the spelling: the vowels. Everybody agrees that they go -a-u-a- (I’m using the dashes to denote possibly missing consonants for now).You may have noticed the 2 different spellings of The Word in Hebrew above:חֲנֻכָּה: the original word, in which the /u/ portrayed in נֻ (/nu/) is a short one. Biblical Hebrew distinguished between long vowels, short vowels, and half-sized vowels. Due to Biblical Hebrew syllable-structure shenanigans, the /u/ is short.חנוכה: the modern way of writing the word. The נו (/nu/) would have denoted a long vowel in Biblical Hebrew … but Modern Hebrew does not distinguish vowels by length. The first /a/ (in חֲ) used to denote a half-length vowel. Since vowel-length doesn’t mean anything anymore in Hebrew, both /a/ are equal.Therefore, in Modern Hebrew, חנוכה = חֲנֻכָּה.That covers the vowels. Next, the bits where everybody who knows even a bit of transliteration would agree on:There’s only 1 /n/. That means it’s -anu-a-.There are 2 /k/ after the /u/. That’s because the Hebrew is כָּ. You see the little dot in the middle? That used to mean that the sound used to be geminated. We don’t really observe gemination in Modern Hebrew anymore, except that in some letters (v, f, ch) the little dot (dagesh) denotes something very important.In case you don’t want to double the K, because the language that you’re using, AKA English, that doubling means absolutely nothing, you can skip it.This leaves us with -anuk(k)a- as a definite spelling so far.This is where things get murky. Because you see … this is when the transliteration rules start falling apart by way of a long tradition of transliteration as well phonology rules across several languages in the duration of about 2000 years.The beginning ח: is it h, kh, or ch? Frankly, it could be any of these.KH: This is the transliteration of a sound in Hebrew that no European language has or has had. Standard Modern Hebrew doesn’t have it anymore, but it’s still considered an acceptable, very common variance of the consonant ח. In linguistics, it’s written as [ħ], and in Semitic studies, it’s written as ḥ (an h with a little dot below it). You can listen to it [here on Wikipedia]. This is the classical, old-fashioned, origins-faithful spelling … which looks very very wrong: Khanukka-. Weird, right? Still correct.If you listened to the recording, you might think it sounds between an /h/ and an /x/ (as in ‘ch’ in the Scottish Gaelic word for lake ‘loch’), depending on which sound you preferred.H is how the Greeks transliterated the letter ח in the Bible (such as in the second h in the word ‘Bethlehem’)CH is how Standard Modern Hebrew pronounces via the Ashkenazi pronunciation of Yiddish.So if you spell it with a KH, you’re an out-of-date traditionalist; if you spell it with an H, you’re faithful to the name of the holiday in your own language, and if you spell it with a CH you’re faithful to the Standard Modern Hebrew pronunciation (and probably have family who speaks either Hebrew or Yiddish).Possible, correct options so far:Khanuk(k)a-Hanuk(k)a-Chanuk(k)a-Which leads us to the very last dash! Is there an H at the end? Should there be an H at the end?This is where it gets the most complicated, because it requires some background in Hebrew noun-noun constructs.The word ‘חנוכה ‘ is an actual word in Hebrew that means ‘inauguration, dedication, consecration‘ according to morfix.co.il (the Hebrew-English-Hebrew web translator). Since Hebrew is a gendered language, The Word is a feminine noun. A lot of feminine nouns in Hebrew end with what can be directly transliterated as ‘-ah’, or, in Hebrew, a word-final ‘ה‘ (the name of this letter is either He or Hey, depending on how much official Hebrew education the person had).This Hey is silent. It hanging around does not mean there’s an /h/ sound in the word. All it does is tell the user of the language that they should pay attention to this word, because in noun-noun constructs, the Hey becomes a Tav (or Taf). This was ‘inauguration of [noun]’ is חנוכת-בית (khanukkat-bayit in pefect translit; ‘bayit’ is ‘house’ or ‘home’).So, it’s really up to you whether to add that last H or not.What you should be careful of, probably, is mix-and-matching. Khanuka is just outright weird, because you’re mixing a bunch of translit styles – going from extreme translit mode (KH) to mild mode (one K, no H). Chanuka also looks strange, because the CH is also somewhat strict-ish translit.This all means that these are all the correct spellings in English, from a Hebrew standpoint, from most-strict transliteration to the most permissive:KhanukkahChanukkahHanukkahChanukka (h is silent, double-k still serves a phonetic purpose that I didn’t bother going much into)HanukahHanukkaHanuka (as much as it makes me twitch)You’re welcome, and may you all confuzzle everybody you come across! -- source link

Tumblr Blog : kazoobard.tumblr.com

#judaism