encyclopedia-amazonica:Nakano Takeko - The swan song of samurai warrior womenIn 1868, Japan was faci

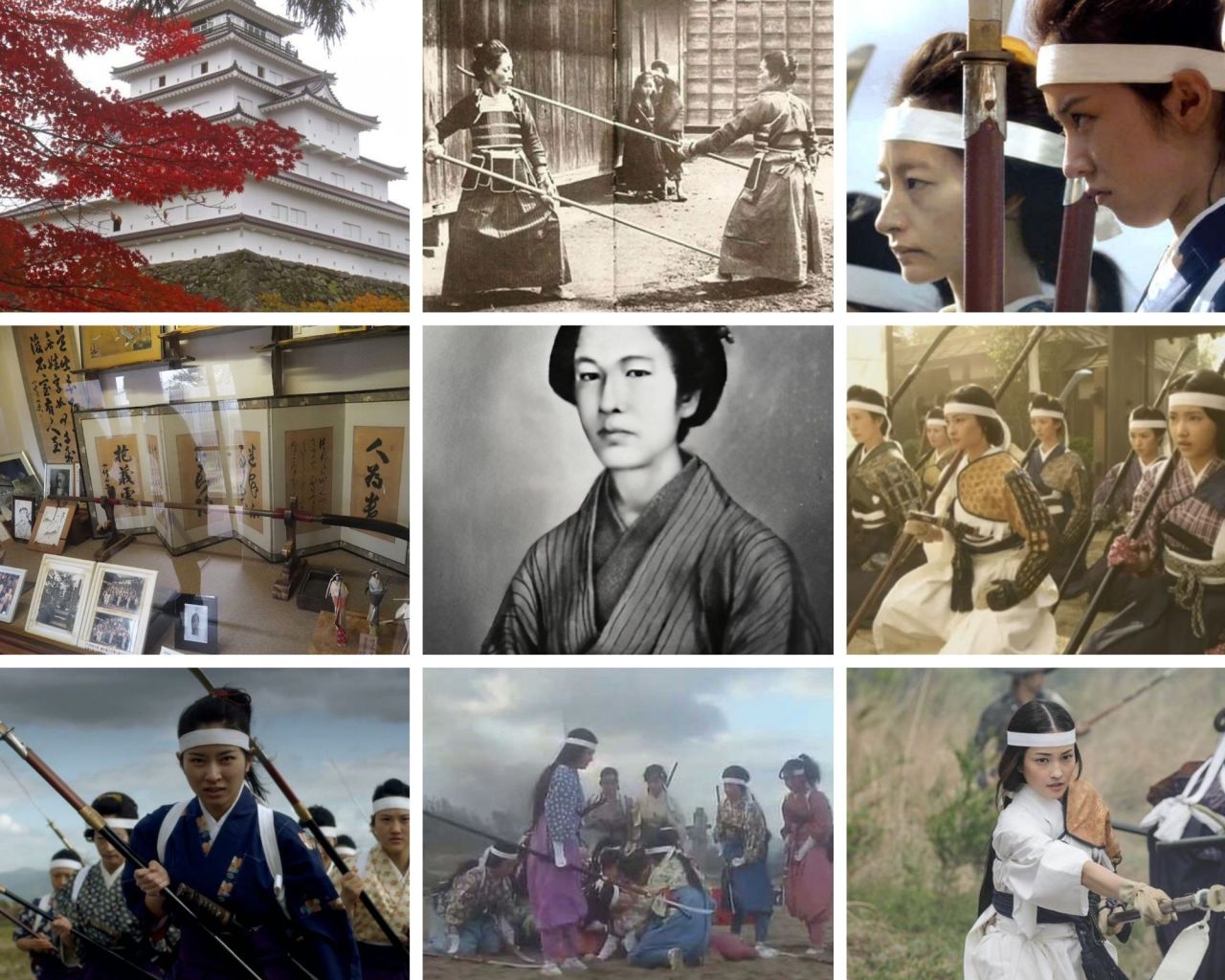

encyclopedia-amazonica:Nakano Takeko - The swan song of samurai warrior womenIn 1868, Japan was facing drastic political changes. The arrival of American ships in 1853 forced a country who had been closed to foreigners for the last two centuries to open. This led a to movement of distrust toward the Tokugawa shogunate and culminated in the restoration of the emperor’s power.Some clans and domains didn’t accept this situation and stayed loyal to the shogunate. Such was the case with the Matsudaira of Aizu. In autumn 1868, Aizu came under attack by the imperial troops. Aizu was a conservative domain, its warriors strictly followed the samurai traditions. The women were trained with the naginata and to knew how to use a dagger for ritual suicide or self-defense. When the imperial troops arrived, some women decided to commit suicide, taking with them their children or elderly relatives to avoid being a burden for the defenders or fearing capture. A woman named Kawahara Asako beheaded her daughter and stepmother before taking her naginata to fight against the invaders. She survived her first sortie and was ultimately forced to withdraw to the castle.Other women decided to fight, and one of them was Nakano Takeko (1847-1868). Takeko was 22 when the battle began. The daughter of an Aizu councilor, she excelled in martial arts, poetry and calligraphy. On October 8, the alarm bell rang as the enemy managed to enter the town. Takeko immediately joined, with her mother, Kôko, and her 16 years old sister Masako (also sometimes called Yûko), a group made of men and women to fight the intruders.The defenders, however, decided to close the castle gates and the three women found themselves blocked outside. They decided to join the outpost were the Aizu soldiers were stationed and were joined on the way by other women. Each of them had decided to cut their hair like a male samurai. They wore a white headband and a hakama. They had two swords at their belts and were armed with a naginata.Between 20 and 30 women ultimately joined was later called the joshigun or “women’s unit”. Takeko went to the leader of a squad of Aizu soldiers and asked to be allowed to fight. He refused at first, arguing that if the enemy saw women among the Aizu soldiers, they would think that the domain was on the verge of defeat. Takeko then threatened to commit suicide if she wasn’t allowed to fight. She and the other women were placed under commander Furuya who ultimately accepted their demand.The next day, the Aizu forces and the joshigun, attacked the imperial troops at Yanagi bridge, hoping to break through and go back to the castle. The women were unafraid, even if they had to charge at men equipped with firearms. When the enemies saw that they were women, they gave at first the order to capture them alive. Takeko killed 5 or 6 men with her naginata, but was shot in the head and/or in the heart and died. Her younger sister didn’t want Takeko’s head to be taken by the enemy as a trophy. She thus tried to cut it, but couldn’t do it and asked an Aizu soldier for help. Masako managed to bring her sister’s head to Hokkai-ji temple where it was buried.On October 13, the surviving women arrived to the castle with Hirata Kochô as their leader. They kept fighting and force some of them participated in the defense as sharpshooters. Masako was among the members of the joshigun who survived the castle’s fall. She went afterward went to Hakkodate, Hokkaido. Today, Takeko’s naginata is kept at Hokkai-ji. A statue as been erected in her honor in the town of Aizu. Each year, young women play the role of the jôshigun at the Aizu festival.Takeko’s death poem, that she had tied to her naginata, was: “I would not dare to count myself among all the famous warriors - even though I share the same brave heart”.She was among the last samurai warrior women. Women took arms during the 1877 Satsuma rebellion to prevent the samurai status’ and privileges from being abolished, but to no avail.Here’s the link to my Ko-Fi if you want to support me.Sources: Shiba Gorô, Remembering Aizu: the testament of Shiba Gorô“Samurai warrior queens” documentary Wright Diana E., “Female combatants and Japan’s Meiji restauration: the case of Aizu “Yamakawa Kikue, Women of the Mito domain -- source link

Tumblr Blog : encyclopedia-amazonica.tumblr.com