alexalfurinn: εablative-absolute:sparks-fly-upward:7 Misconceptions in Greek Mythology!These are jus

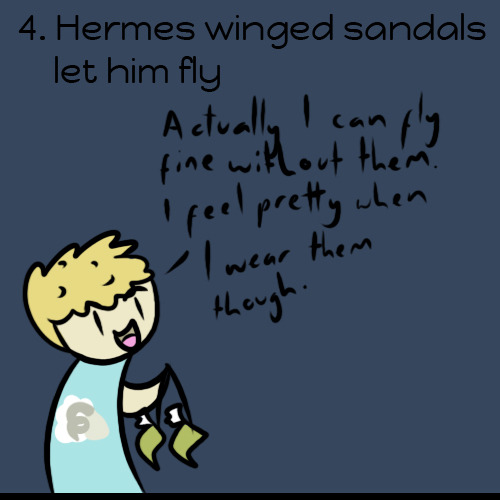

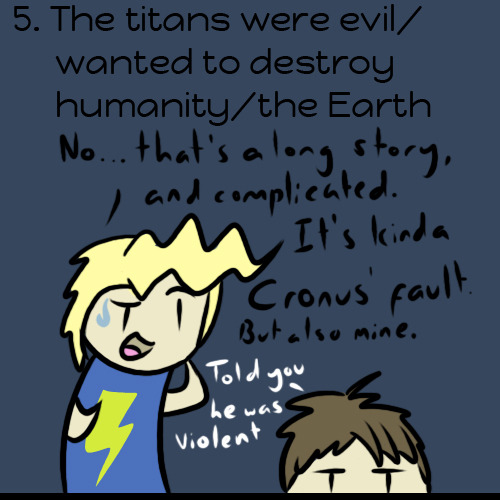

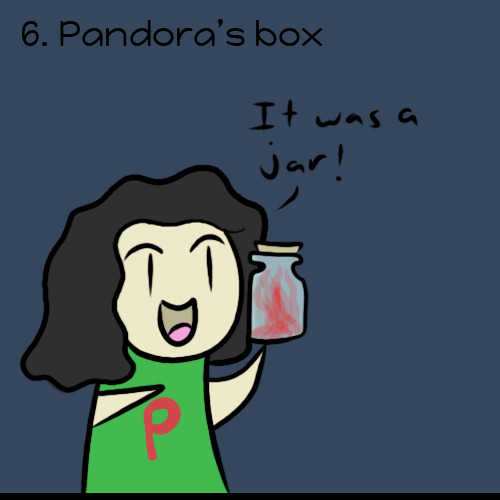

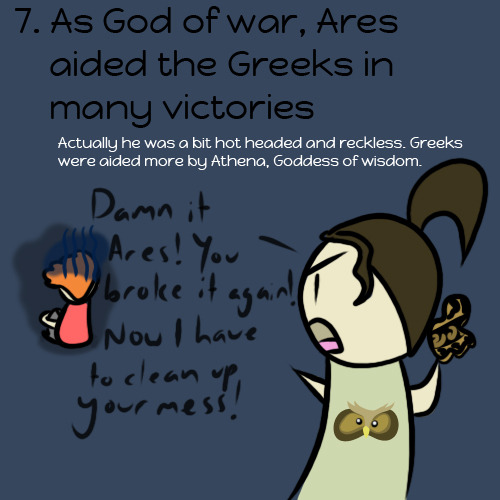

alexalfurinn: εablative-absolute:sparks-fly-upward:7 Misconceptions in Greek Mythology!These are just a small selection of things I’ve seen and heard people thinking on the internet. A lot of this comes from Greek Mythology based media, which has become increasingly popular. So I’m here to clear things up!Hades was really good, he did all he could to make the underworld a comfortable place for his wife Persephone to live. He also was faithful to her and never sought out souls for his underworld, but waited for them to come to him. A lot of his perception as evil comes from the modern interpretation of Satan.There are some that seem like exceptions to this one, firstly is Heracles, who actually was just intensely determined and no stronger than a mortal could be if they poured effort into it. Dionysus is the other, as he became an olympian. But he generally gets a pass from historians, since Zeus actually gave birth to him, and that’s said to have an impact.Hercules is Roman. You can imagine I cringe every time I hear his name in the Disney movie since he’s the only Romanised name in the whole thing.Hermes was often painted with his sandals to identify him and this leads to the idea that he needs them to fly.So basically the olympians started the big war, but Cronus kind of had it coming since he ate all of his children in order to stop the possibility of them overthrowing him like he had done to his father. So when Zeus freed all his brothers and sisters, that’s exactly what he did.Yup.In most texts, Ares almost always was on the losing side of wars, whereas Athena was almost always on the winning side. Turns out in war you need more brains than brawn. At least you got Aphrodite, buddy.Okay, let me just stop you RIGHT THERE at number 1. Hades was NOT “really nice.” He kidnapped and raped a child. If Hades had wanted to make Persephone comfortable, maybe he could have started by NOT KIDNAPPING HER IN THE FIRST PLACE. Honestly, the kidnapping and rape of Persephone is the MOST COMMON myth about Hades, yet it always gets ignored on these sorts of posts.In trying to correct the association of Hades with the devil and the embodiment of evil, people often claim he was actually really nice. He wasn’t. He wasn’t the devil, certainly, and was never considered in ancient times the embodiment of sin, just someone who watched over the dead. However, he was never, by any stretch of the imagination, a nice guy.Please think about what you’re saying when you claim Hades was a nice, chill guy who was cool to Persephone because he didn’t cheat on her. Think about little Persephone, who was small enough to sit on her mother’s lap on Mount Olympus — which is why she never had a throne there — at the time of her kidnapping. Hades was no better than Zeus, even if he wasn’t serial. Honestly, none of the Gods or Goddesses were very nice except for Hestia, and if you want to challenge me on that, go ahead.TL:DR - HADES IS NOT A GOOD GUY, HE IS A RAPIST AND A PEDOPHILE.Hades did certainly kidnap an unwilling Persephone, but the text doesn’t say anything about sexual violence. The Homeric Hymn to Demeter reads: χάνε δὲ χθὼν εὐρυάγυια Νύσιον ἂμ πέδιον, τῇ ὄρουσεν ἄναξ Πολυδέγμων ἵπποις ἀθανάτοισι, Κρόνου πολυώνυμος υἱός. ἀρπάξας δ᾽ ἀέκουσαν ἐπὶ χρυσέοισιν ὄχοισιν ἦγ᾽ ὀλοφυρομένην ἰάχησε δ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ὄρθια φωνῇ, κεκλομένη πατέρα Κρονίδην ὕπατον καὶ ἄριστον. Then the wide-pathed earth yawned in the plain of Nysa, and there the lord who receives all, the many-named son of Kronos, rushed forward with his immortal horses. He snatched the constrained girl upon golden carriages and led her away, lamenting. She shouted shrilly with her voice, calling her father, the son of Kronos, the highest and best.I think a lot of the confusion comes from the various translations of ἁρπάζω (seen here as an aorist participle in the masculine nominative singular: ἁρπάξας). In Greek it means “to seize” or “to snatch,” and older English translations will use the verb rape, which at the time was equivalent. Consider also the poem “The Rape of the Lock” by Alexander Pope, in which a character cuts off a piece of a woman’s hair without her consent.It’s not difficult to see how the English verb transitioned from its earlier to its current meaning, especially since there are implications of unwillingness. But I don’t think that’s present in the Greek word?The poem also doesn’t state how old Persephone is? All we know is that she was frequently called Κόρη, a word that means “girl.” And if the poem is meant to represent Ancient Greek girls being married off, which is probably likely given that Zeus arranged this with Hades beforehand, then we can guess that she was probably around 14. Which, yes, is vile and inexcusable when we think about it, but was completely normal for the audience who would’ve been listening to this poem. There’s cultural context to consider, even if it’s uncomfortable for us.If you haven’t already, I would recommend reading the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, which is the basis for the Demeter and Persephone myth. The English translation can be read right next to the Greek text, just click load in the bar that says “English (Hugh G. Evelyn-White)”Now I know I wrote a post recently defending the fact that we should be able to interpret Greek myths how we want because that’s what the Ancient Greeks did. But I also stressed that we have to do that while bearing in mind the context at the time. It’s a little daft to discuss whether or not Hades was a ‘nice guy’. He was a god. They didn’t have the same standards even at the time. Social justice is an entirely intellectual, modern, human concept; don’t project it at a supernatural figure of myth unless you’re going to consider the literary versions of that myth in detail. It’s also ridiculous to ask 'how old’ Persephone was; did the gods count in years? No. It’s like the difference between Narnia and the real world. The gods’ 'aging’ will have taken place over thousands of mortal years, before mortal time was even a thing, and it is clear that they eventually stopped aging at varied points, and assumed physical forms that corresponded to their status and their significance to mortals (i.e. Zeus is portrayed as older because he’s the 'king’ and 'father’ figure; Athena, Hestia and Artemis, the virgin goddesses, are often portrayed in art as more athletic than Hera, Demeter and Aphrodite).(If we’re going to play that game, though: my amalgamation of most versions of this story is that Hades accepted an arranged marriage, kidnapped the girl as he was instructed by the king of the gods, showered her with honours, did not have sex with her until she was ready, and was extremely patient with an intransigent and psychotic mother-in-law. Bad by our standards, yes, but that makes him much more noble than many real Athenian males and certainly than his brother Zeus, who did not kidnap women or boys to marry them and do honour by them, but to have quickies or to use them as sex slaves. It is also rather arrogant to decry arranged marriage in this way when many non-white communities continue to practise it; 'organised by the father’ does not in principle mean 'against the girl’s will’ and we shouldn’t judge it by the standards of modern feminism and/or assume that any girl who agrees to that has 'internalised’ something.)The story of Hades & Persephone is not to be taken at face value on any level. Firstly, it was in origin a myth to explain the seasons. Secondly, our first version of it (the Homeric Hymn to Demeter) is a literary version of that myth, in which the poet deliberately selects the elements he wants to emphasise to create not just a good story but his version of it. Thirdly, it is meant to represent society’s institutions on a symbolic level. It does indeed represent fathers arranging their daughters’ marriages - but no one took it literally and thought that the right way to do it (or even a possible way to do it) was to leap out of the earth and carry the girl in a chariot. The post above mine simplifies the poem’s portrayal a little. In Greece (certainly in Athens but I imagine elsewhere) the penalties for adultery (which included sex with someone else’s wife and with an unmarried citizen girl) were extremely high, and the girl was not held at fault if she was held to be unwilling. At least in drama, they represented 'unwillingness’ by her showing signs of a physical struggle; the Greeks did not have the concept of 'too scared to say no’ it seems, but hey, for over 2000 years ago, I think even just by recognising that much they’re doing better than America is at the moment.The Homeric Hymn to Demeter is, after all, about Demeter. It emphasises Demeter’s unwillingness to let her daughter get married - which was dysfunctional and obstructive to the natural order of things. Girls got married; Demeter’s behaviour was selfish and unreasonable (although gods are allowed to be this) - she tried to starve all humans to death because she wanted her daughter to be the only exception to the marriage custom - and later tellings of the story suggest as much, depicting Demeter - as do many modern versions - as interfering in Persephone’s independence, growth to maturity, and marital happiness. The Hymn has sympathy for Demeter’s behaviour, which must have reflected the behaviour of at least some mothers in antiquity (women complaining about being separated from their families by marriage was a trope in ancient tragedy), but nonetheless shows that it cannot stand.In the Homeric Hymn, Persephone is shown screaming for help when she is kidnapped - as is appropriate, since she can’t be portrayed as willing and besides, Demeter wants Persephone to be just as unwilling to be separated from her. As the poem continues, Persephone’s reluctance is continually stressed, but each time it gets a little more ironic. At the start of the poem it says that Persephone was with some nymphs when she was kidnapped and no one heard her cry for help (except Hestia, who didn’t know whose cry it was, and Helios, the sun), i.e. she was off wandering on her own, which suggests she was sexually curious. When Persephone tells her story to her mother (and when a character repeats the narrative, we have to be very attentive to differences), she says that she was with Athena and Artemis (eternal virgins - 'look, Mum, I only hang out with virgins, I won’t be corrupted!’). Athena and Artemis were not even there - and if they were, why did they not hear her? She also says Hades 'forced’ her to eat the pomegranate seeds - but the narrative described him doing so quite coyly, not violently, and does not suggest she was forced at all. Persephone is obviously trying to cover up the fact that she is now happy to be married to Hades. Additionally, the poem never once mentions the two consummating their relationship, and Persephone is described as rejoicing to hear that a) she will get to go back and forth between the underworld and upper world, b) she will be an honoured queen. The implication is that when she eats the pomegranates Persephone becomes an adult, a queen in her own right, with her own powers, of which her mother tried to deprive her. Later versions of the Hades and Persephone myth portrayed Persephone as even happier. Vergil (the Roman poet) explicitly stated that Persephone did not want to go back to Demeter. The fact that Persephone’s sexual maturity - usually associated with flowering - is represented symbolically by the barrenness of the earth is an extremely fascinating line of thought, which should be considered in those terms. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : sparks-fly-upward-blog.tumblr.com

#greek mythology#classics#rape#matrimony#homeric hymns#demeter#anthropology#culture#sententiae