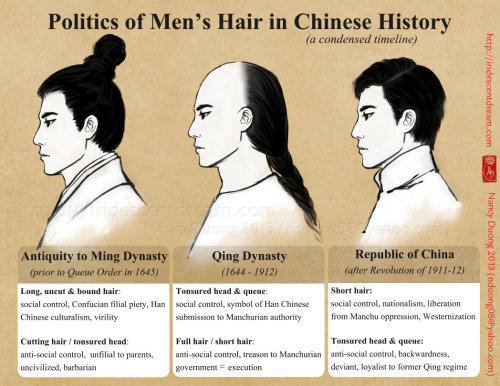

Politics of Men’s Hair in Chinese History (a condensed timeline) ***** References:Manchu

Politics of Men’s Hair in Chinese History (a condensed timeline) ***** References: Manchus And Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861-1928 (Studies on Ethnic Groups in China) By Edward J. M. Rhoads Hair: Its Power and Meaning in Asian Cultures edited by Alf Hiltebeitel, Barbara D. Miller The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History by Michael R. Godley China Made: Consumer Culture and the Creation of the Nation By Karl Gerth Sources of Chinese Tradition: Volume 1: From Earliest Times to 1600 By William Theodore De Bary, Irene Bloom, Joseph Adler ***** Social control (according to Merriam-Webster): the rules and standards of society that circumscribe individual action through the inculcation of conventional sanctions and the imposition of formalized mechanisms ***** Ming Dynasty and dynasties prior (1644 and before) “In Chinese consciousness of hair, moral discipline is more perceivable than sexual restraint. Cutting hair is more critical than the change of hair style. In the periods under consideration, hair cutting meant social control, not only supported by the conventionalized and morally approved fashions, but also regulated and supervised by the political authorities.” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, pg. 138) “Long before the Manchu conquest, Han males had become accustomed to the practice of binding up their long hair on the top of their heads. This custom is inferred by such idioms as ‘to bind hair when starting school’ (sufa shoushu), or ‘to bind hair while being a soldier’ (Jiefa congrong). When a student was twenty years old, he ought to have a ‘caping ceremony’ (guanli) in which he changed his child’s headdress to an adult’s, demonstrating his entrance into the mature world. This tradition can be traced back to the Zhou dynasty (1100-256 B.C.) (SSJZS 1:945).” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, 124) “Under the Ming regime, the ceremony was adopted by more social categories than the scholar-offical class (Zhang 3:1377-87). Ming men, once capped, let their hair grow long, and wore it in elaborate fashion under horsehair caps (Ricci 1953:78).” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, 124) “One of the greatest obstacles confronting early Chinese Buddhism was the aversion of Chinese society to the shaving of the head, which was required of all members of the Buddhist clergy. The Confucians held that the body is a gift of one’s parents and that to harm it is to be disrespectful toward them. The questioner said, ‘The Classic of Filiality says, ‘Our body, limbs, hair, and skin are all received from our fathers and mothers. We dare not injure them.’ When Zengzi was about to die, he bared his hands and feet. But now the monks shave their heads. How this violates the sayings of the sages and is out of keeping with the way of the filial!’” (Adler, pg 423) “Although some modern writers have claimed that Chinese resisted hair-cutting because of their reluctance to part with a gift handed down from their ancestors, the heads of boys were, in fact, shaved even during the Ming Confucian revival, a practice which continued throughout the Qing.[32] It could, therefore, be that head-shaving was perceived by adults as an insult.” (Godley) “The cutting off of hair in fact accompanied castration in ancient China, and hair was cropped as a form of punishment right up to the eve of the Mongol invasion. From cases reaching the Board of Punishments in the early Qing, we do know that members of certain heterodoxical sects attached magical potency to their long hair.[33] As Philip Kuhn concluded in his study of the role of sorcery and ‘soul-stealing’ in the 'queue-clipping’ outbreak of 1768, a century after the conquest, the tonsure was still far more important, symbolically, than the queue.” (Godley) “This case shows how hair became a means of social control and a focus of cultural and political conflict. In traditional China men’s long and bound-up hair epitomized the Confucian norm of filial piety, Han culturalism, and magical power.” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, 138) Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) “During the Qing dynasty, the shaved forehead and queue symbolized Manchu autocratic authority and its cultural dominance, though Han Chinese still held a moral and respectful attitude toward their hair.” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, pg. 138) “The queue was the male hairstyle of the original Manchus, a variant of the way men of the northern tribes, including the Jurchen, had traditionally worn their hair; it involved shaving the front and sides of the head, letting the rest of the hair grow long, and braiding it into a plait.” (Rhoads, pg. 60) “The regent Dorgon, uncle of the young emperor Fulin […] upon occupying Nanjing […] issued a decree formally requiring all Chinese to shave their foreheads and plait their hair in a queue like the Manchus. Chinese men had to conform to the new rulers’ hair style. Disobedience would be ‘equivalent to a rebel’s defying the Mandate (of Heaven)’ (ni-ming) (SZSL 17:7b-8).” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, 125) “…a Han male’s queue reflected the Manchus drive to submit Hans to the minority’s political and cultural hegemonies and its symbolic standardization of the people’s political ideology.” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, pg. 124) “Having accepted the Confucian notion that the ruler was like a father and the subjects like his sons, Dorgon emphasized the physical resemblance between the Manchus and the conquered Chinese. The affirmed purpose was to make Manchus and Hans a unified body. Being afraid of inspiring any anti-Manchu imaginations and actions, the Qing rulers enforced the hair cutting policy and persecuted hair growers without mercy.” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, 125) “A slogan of the tonsure operators was ‘Keep your head, lose your hair; keep your hair, lose your head’ (Wakeman 1975a:58), which epitomized the ruthlessness of the Manchu’s hair cutting.) (Hiltebeitel and Miller, 125) “The only ones exempt [from the Queue Order of 1645] were men in mourning, young boys, Buddhist monks (who shaved off all their hair), and Taoist priests (who let their hair grow). All other Han males in Qing China were coerced into abiding by the requirement.” (Rhoads, pg. 60) After Revolution of 1911-1912 “After the fall of the Qing court, short hair replaced the queue style, embodying nationalism and Westernization.” (Hiltebeitel and Miller, pg. 138) “The men’s hairstyle, which the Qing originally required as a badge of subservience to Manchu rule, was, not surprisingly, the revolutionaries’ first target. Despite several years of open agitation by political and social reformers for its removal, the queue requirement had remained in effect until two months into the revolution. Even then the Qing had only permitted, but did not compel, its male subjects to cut their queue and wear their hair short in the Western (and Japanese) style of the day.” (Rhoads, pg. 252) “The Republicans were not satisfied with this eleventh-hour, half-hearted measure; they insisted on universal, mandatory queue-cutting. Thus, in the four months between the Wuchang uprising and the Qing abdication, wherever the revolutionaries took power, one of the first decrees they issued was for the removal of the queue as a sign of loyalty to their regime.” (Rhoads, pg. 252) “To the Republicans’ distress, their policy of universal mandatory queue-cutting did not always meet with general approval, not necessarily because the people were opposed to the revolution but because after more than two centuries, they regarded the Manchufied hairstyle as an integral part of their cultural tradition. As a result, the queue-cutting orders were often ignored; their unrealistically short deadlines, unmet.” (Rhoads, pg. 252) “For most Chinese, the forcible removal of the queue was, as one observer put it, a ‘humiliating disfigurement.’ In their eyes, the queue was less a ‘badge of conquest’ and more a badge of nationality and identity (Crow 1944: 22). These Chinese had forgotten the original terms under which the hairstyle had been imposed and had no idea that it could signify allegiance to the Qing.” (Gerth, pg. 91) “In Changsha, the provincial capital of Hunan, as in many Chinese cities and towns, retention of the queue was viewed as an explicit sign of traitorous allegiance to the Manchus”. (Gerth, pg. 92) “Although the queue was on the way out, there was, in fact, some opposition to 'foreign hair.’ One Hunan official, who listed all the advantages of a queueless head, nevertheless resisted Japanese and Western styles. Some tried to pile their hair on top, while others adopted a half-cut which resembled a mop. A few had bets each way and, having experienced the moment of liberation, tied their braids back on.” (Godley) “When the directives for voluntary compliance failed of their purpose, the revolutionary governments generally resorted to coercion. In Zhejiang, local officials in Jiaxing and Hangzhou sent out soldiers armed with large shears to cut any remaining braids on sight; they posted such ‘queue-cutting brigades’ at the city gates to catch unwary villagers entering from the countryside.” (Rhoads, pg. 252) “Queue-removal was something of an official crusade in the early years of the Republic. It was deemed a prerequisite for voting in one province, while as late as 1914 Beijing authorities renewed their pressure on the recalcitrant inhabitants of that city. Now it was the police that cut the queues off anyone arrested.” (Godley) “By the late 1930s… [though the queue]… could be glimpsed occasionally in such remote places as a market town in Anhui, it had become a noteworthy rarity. Otherwise, the hairstyle of Chinese men had been completely ‘de-Manchufied.’” (Rhoads, pg. 253) -- source link

Tumblr Blog : nannaia.tumblr.com

#chinese culture#historical fashion#queue hairstyle#ming dynasty#ancient china#qing dynasty#hair fashion#infographics