themyskira:Women of the Italian Renaissance | LAURA CERETA (1469-1499) Unlike most

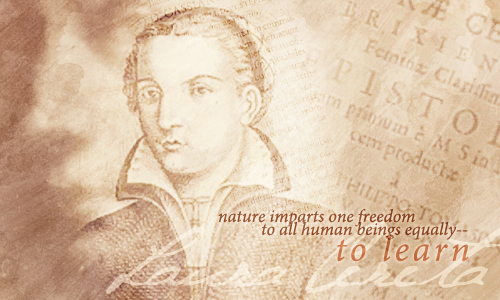

themyskira: Women of the Italian Renaissance | LAURA CERETA (1469-1499) Unlike most female humanists of her time, Laura Cereta’s early education came not from her father or some distinguished male tutor, but from women. Born into an upper middle class family, the daughter of Brescian attorney and magistrate Silvestro Cereta, at the age of seven Laura was sent away to a convent for schooling. She frequently struggled with insomnia, and learned to fill her sleepless nights with writing, studying and embroidery. She returned home for good at the age of 11, having mastered Latin grammar. At 12, she found herself almost solely responsible for running her father’s household and supervising her five younger siblings. “It was my lot,” she wrote, “to grow old when I was not far from childhood.” She continued to find solace in her studies, attending lectures in what little time she had to herself and frequently reading late into the night. At 15 she married a Venetian merchant, Pietro Serina, only to be widowed a mere year and a half later. Many of her letters to Pietro survive, revealing frustrations, disillusionment and loneliness as well as flirtation and genuine affection. In one letter, dated August 13, 1485, she responds indignantly to her husband’s suggestion that she does not love him enough: But as to your saying that I don’t love you very much, I don’t know whether you’re saying this in earnest or whether I should realise that you’re joking with me. Still, what you say disturbs me. You are measuring a very healthy expression of a wife’s loyalty by the standard of the insincere flattery of well-worn phrases. But I shall love you, my husband. … Let women without means, who worry and have no confidence in their virtue, flutter their eyelashes and play games to gain favour with their husbands. … I don’t want to have to buy you at such a price. I’m not a person who lays more stock in words than duty. I am truly your Laura, whose soul is the same one you in turn had hoped for. Her grief at Pietro’s death was real, and she once again sought consolation in academia, engaging in discussions with fellow humanists and cultivating friendships with learned women. She delivered her first public oration at 18, and the following year completed a book containing 82 letters and a comic dialogue. Several early biographers even claim that she spent seven years teaching moral philosophy at the University of Prada, although there are no public records to verify this. And she accomplished all this in a time when Venetian women were not supposed to have a public voice, when the ideal woman was described as silent, submissive and obedient. Unsurprisingly, Laura had numerous detractors, both male and female. Some, like the humanist Eusebio, claimed that her articulate letters had in fact been written by her father. Michael Baetus accused her of plagiarising a book on astronomy, refusing to believe that she might be capable of making her own observations on the movements of the stars; Laura countered him by providing a description of the motions of the Moon and planets four days prior, far too recent information to have yet been published in any book. At the other end, she faced men who sought to justify her intelligence by declaring her to be unique among women: these claims she addressed in a withering letter, arguing that women were equally as capable as men and citing dozens of specific examples from mythology as well as ancient and recent history. An early feminist, Laura was critical of the oppression of women in marriage and passionate in her belief that women had the same right to an education as men. Writing in 1488 in response to those who attacked her writing because of her sex, she declared, I am a scholar and a pupil who has been lulled to sleep by the meagre fire of a mind too humble. I have been too much burned, and my injured mind has accumulated too much passion; for tormenting itself with the defending of our sex, my mind sighs, conscious of its obligation. For all things — those deeply rooted inside us as well as those outside us — are being laid at the door of our sex. In addition, I, who have always held virtue in high esteem and considered private things as secondary importance, shall wear down and exhaust my pen writing against those men who are garrulous and puffed up with false pride. I shall not fail to obstruct tenaciously their treacherous snares. And I shall strive a war of vengeance against the notorious abuse of those who fill everything with noise, since armed with such abuse, certain insane and infamous men bark and bare their teeth in vicious wrath at the republic of women, so worthy of veneration. She died suddenly of unknown causes at the age of 30 and was honoured with a public funeral and festivities in Brescia. She left behind her a considerable legacy, with several hundred pages of her writing surviving. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : themyskira.tumblr.com

#laura cereta#renaissance italy