Imagine a person tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered,with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like

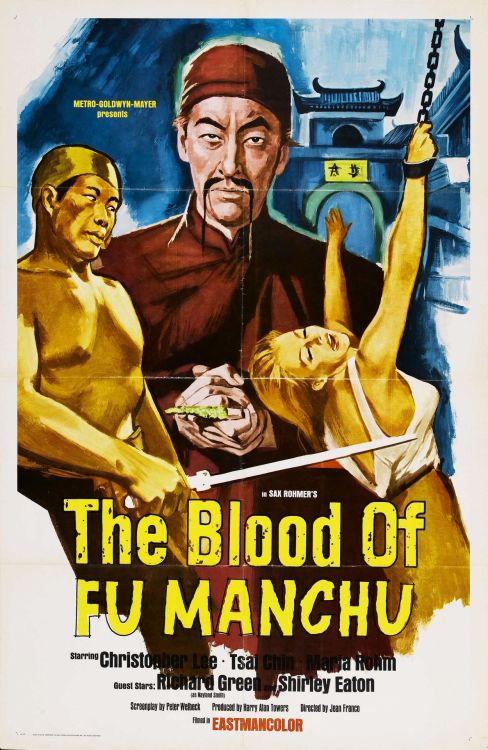

Imagine a person tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered,with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present, with all the resources, if you will, of a wealthy government-which, however,already has denied all knowledge of his existence. Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man. -Sax Rohmer,The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu (1913) Yellow Peril was a colour metaphor for race that originated in the late nineteenth century with immigration of Chinese as coolie slaves or labourers to various Western countries, notably the United States, and later associated with the Japanese during the mid 20th century, due to Japanese military expansion. When The Mystery of Dr. Fu-Manchu was published in London in 1913, Sax Rohmer (1883-1959) moved from literary obscurity into a fame that lasted for almost fifty years. The central, recurring conflict of these thrillers- Dr. Fu-Manchu’s schemes for global domination-rewrot the master narrative of modern England, inverting the British Empire’s racial and political hierarchies to imagine a dystopic civilization dominated by evil Orientals. Although the rhetoric of these novels exalts twentieth-century England as a source of a desirable quality relating to progress, knowledge, and virtue. Dr. Fu-Manchu’s near-total appropriation of sociopolitical and technological systems points to the negative capabilities of industrialization and modernization. Rohmer’s Fu-Manchu novels forge an intimate connection between racial identity and the various promises of twentieth-century modernity. In translating the conditions of Western modernity into a battle for racial dominance, Rohmer gives expression to the cultural anxieties and dislocations that high modernist authors were concerned with. Rohmer’s depictions of a premodern, barbaric, and anti- Western China exist with anxieties about China’s very own modernization. In 1911, the year in which the first Fu- Manchu stories were serialized, sociopolitical revolution in China ended the Manchu dynasty and Confucian social order, resulting in the founding of Sun Yat-sen’s Chinese Republic in 1912 and eventually leading to the formation of Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalist China in 1928. The racial oppositions that heighten the Fu-Manchu novels’ melodramatic aesthetic also create a discursive space for Sax Rohmer’s complex negotiations of English modernity. By pitting Fu-Manchu’s loathsome criminal genius against England’s inherent goodness, Rohmer’s novels make a dual critique of the modern West’s obsession with innovation, global sovereignty, and the acquisition of knowledge. Rohmer’s unwitting representations of English failure, whether at the level of individual characters or of larger social structures, are the points where the Fu-Manchu novels intersect most provocatively with the narratives of high modernism. Fu Manchu has been made into a bunch of films and inspired many villains in different media. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : teenagesmog.tumblr.com