Kisaeng (finally) - The topic of ‘kisaeng’ contains old and new cultural dialogue,

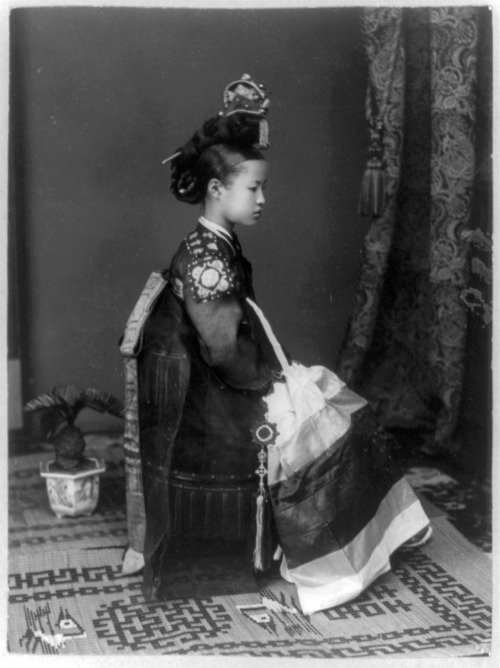

Kisaeng (finally) - The topic of ‘kisaeng’ contains old and new cultural dialogue, colonialism, gender identities, and the modern process of Korean society coming together. The origins of the Kisaeng are obscure; the History of Koryo describes them as the descendants of the members of a migrant group, the Willow and Water People. The first ruler of the Koryo dynasty (918-1392) had difficulty controlling this group so he had them designated as male and female slaves, sending them to various government offices established throughout the provinces. While the Kisaeng system was established during this dynasty, it was was strengthened in the following Choson dynasty (1392 –1897), and shared strong links to the official ideology, Confucianism. Under the Confucian social ethos of Choson society, the roles of women in the upper and middle classes were largely confined to the domestic sphere. Women received only an informal education at home, and were required to observe the Confucian virtues of diligence, filial piety and chastity. It was not possible for the yangban to enjoy music with their wives or other non-professionals, who were excluded from such occasions. Apart from male musicians and boy dancers, kisaeng were the only female group to perform in a number of formal court ceremonies and at the yangban’s private functions. By the end of the Choson dynasty there were three different and strictly classified grades of kisaeng. The highest grade of kisaeng were called the ilp’ae or “Grade 1,” a government position especially created to control the kisaeng group, and which also included female doctors who treated women in the palace. In order to achieve a higher level of performance, kisaeng lived together and trained every day in the court- supported institution of the Kyobangwo Teaching College. The second grade of kisaeng, ip’ae or “Grade 2,” were concubines who had retired at the age of thirty from the highest grade, and who acted as part-time prostitutes and entertained at private parties with their artistic skills. The third grade, samp’ae or “Grade 3,” served ordinary men by singing popular songs, and were forbidden to perform the regular songs and dances of the first-grade kisaeng. Their repertoire consisted mainly of chapka (miscellaneous songs) and sijo; they also practiced prostitution. With the opening of Choson to the outside world in the nineteenth century, the strictly Confucian Choson society was forced to confront the destruction of the traditional order of affairs. The official courtesans, the kwan’gi, were abolished in 1907 by the incoming Japanese colonial power. Thereafter, the highest kisaeng could no longer live at the Kyobangwo ̆n in the palace or governmental offices and the traditional hierarchy of the kisaeng system collapsed. Japanese police did not recognize the traditional hierarchy of kisaeng, but rather treated kisaeng as prostitutes, all equally as sex workers, rather than as skilled female professional entertainers. In 1910, a male teacher of the traditional Korean classical vocal form of kagok, Ha Kyuil, established a private kisaeng institution, the “Institute for Korean Classical Music” to look after and train talented first-grade kisaeng. This establishment can be considered as the origin of the system of kisaeng schools, which trained female entertainers solely for performing traditional music and dance. Another aim for setting up the school was to protect kisaeng aged from 13 to 23 from being sold off to rich men, a common practice during this period. The last generation of kisaeng faced dramatic political and social changes during the colonial period. At a time when Japanese culture was promoted and Western culture was also gradually being introduced, they played a pivotal role in linking old and new in the transformation of Korean culture. However, the image of the first-grade kisaeng during the Choson dynasty as elegant and intelligent was almost replaced by an image of third-grade sex workers, a stigma which affected the kisaeng in the 35 years of the colonial period. This photos were taken during the colonial period (1910-1945) and mostly depict the school while others are a kind of postcard to show modern Japan traditional Korea. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : teenagesmog.tumblr.com