grandhotelabyss:These two controversial, viral Tweets need to be read together, because the latter e

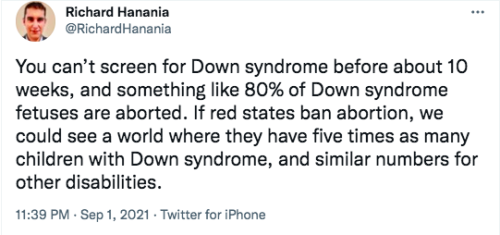

grandhotelabyss:These two controversial, viral Tweets need to be read together, because the latter explains the former’s observation (which I’ve personally observed too) better than the former’s own gloss. The brief and shallow way to put it is that abortion doesn’t weather an intersectional critique very well. The roots of “family planning” in racist and ableist eugenics are too well known not to create a bit of nausea. But we should take a wider view too. Abortion is one issue where the “right” is swimming with the deep current of American culture and not against it. The neoreactionaries—fans, I’m sure, of abortion, being as they are technocrats and biological racists—say, “Cthulhu always swims left” (which explains the putatively Lovecratian fetal image trending yesterday). By this they mean that the state as Hegelian guarantor of rights always finds more and more rights to guarantee and more and more subjects to hold rights in need of protection. The state has been extending rights down the west’s various Great Chains of Being for centuries now; the most advanced theorists currently speak even of the rights of objects. In the showdown between woman and fetus, the fetus is the novel subject in potentia (in this case, literally) and thus at least in theory irresistible to the universal emancipatory project. And since the secular left is just itself Christianity at a later stage of this emancipatory project’s gestation, the conflict here is more a family quarrel about means and ends than an actual contest over first principles. The canonical American poem on this subject, Gwendolyn Brooks’s “The Mother,” is not coincidentally an elegy for embryos written by a black woman of the left:I have heard in the voices of the wind the voices of my dim killed children.I have contracted. I have easedMy dim dears at the breasts they could never suck.I have said, Sweets, if I sinned, if I seizedYour luckAnd your lives from your unfinished reach,If I stole your births and your names,Your straight baby tears and your games,Your stilted or lovely loves, your tumults, your marriages, aches, and your deaths,If I poisoned the beginnings of your breaths,Believe that even in my deliberateness I was not deliberate. Though why should I whine,Whine that the crime was other than mine?—Since anyhow you are dead.Or rather, or instead,You were never made.But that too, I am afraid,Is faulty: oh, what shall I say, how is the truth to be said? You were born, you had body, you died.It is just that you never giggled or planned or cried.I myself was reared in the Catholic Church. Every January, our teachers used to have us schoolkids write letters to our congressional representatives asking them to overturn Roe. In middle school, fresh from the works of Robert Heinlein and Alan Moore, flush with Satanic Shelleyan atheism, I drafted a letter to my teachers objecting to this practice as a violation of my rights, of my freedom of conscience—wonderful Protestant phrases!—but was counseled by a prudent friend, to whom I righteously read it on the schoolbus, not to send it, so I didn’t. In college, at the height of the religious right’s power, I accompanied a girlfriend to a pro-choice protest; tastelessly, we shook clotheshangers at a cathedral. More recently, though, I’ve begun to fear that the terms of the defense—“It’s just a clump of cells!”—has been one source of the liberal imagination’s decay in our time, and that the “clump of cells” rubric has been climbing inexorably up the chain of being to encompass ourselves in all our personhood (call it “the epidemiological view of society”). I am still offended in a Shelleyan way on our human behalf, but offended now by the other side. (Percy Shelley, I mean; for Mary’s opinion about our responsibilities toward our subjects-in-potentia, see Frankenstein.) But I fear in all cases moral absolutes enforced over ethical gray areas by the guns of the state. Abortion, like prostitution or pornography or “harmful speech,” we will never eliminate absolutely, and trying will only make things worse for everybody, especially those with the least ability to bear it. Also in my teen years I read the canonical pro-choice novel, John Irving’s The Cider House Rules, whose moral is more crisply encapsulated in the movie dialogue: “Someone who don’t live here made those rules.” Hegel himself—who was secretly a Catholic thinker, observes Mann’s Naphta, and thus one who tempers mystical moral absolutism with material institutional structure—tells us that politics is a tragic conflict between incommensurate goods, likely, if their conflict is not mediated, to destroy the contending parties. Reblogging what I wrote the last time this came up, eight (not nine, symbol-mongers!) months ago. I have nothing to add at this moment. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : grandhotelabyss.tumblr.com