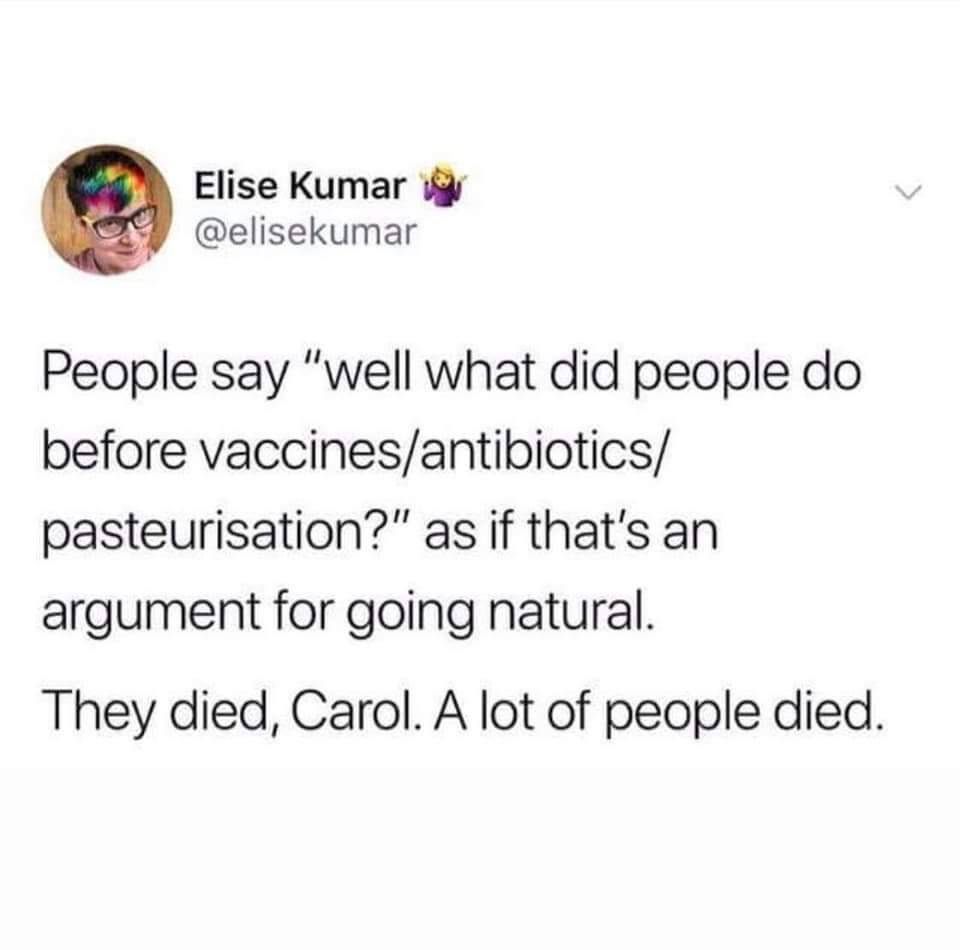

alex51324:beatrice-otter:[screencap of a tweet from @elisekumar:People say “well what did people do

alex51324:beatrice-otter:[screencap of a tweet from @elisekumar:People say “well what did people do before vaccines/antibiotics/pasteurisation?” as if that’s an argument for going natural.They died, Carol. A lot of people died.]If you’re interested in these topics, I can recommend a recent book called A Good Time To Be Born: How Science and Public Health Gave Children a Chance. The author, Perri Klass, starts by laying out just how ubiquitous the experience of child loss was, as recently as a century ago–it was just a thing that absolutely everyone would experience in some form, whether their own child, or a niece or nephew, or a sibling, cousin, or playmate when they were children themselves. Then she uses primary sources like letters and diaries to show that–contrary to what people today like to tell themselves–parents and other loved ones were absolutely devastated by the death of a child; it was something people dreaded from the moment they found out about a pregnancy, and some people who lost a child never got over it. Mortality rates were highest for poor communities, mostly for sanitation reasons, but absolutely nobody was immune; several sitting presidents lost children while in office, when they had access to the most state-of-the-art medical care available at the time. Then she moves in to talking about specific causes of child mortality and the efforts made to combat them. The one that surprised me was “summer diarrhea,” which usually affected children at age 2 or 3–the first summer that they were weaned from breastfeeding, and thus exposed to all of the pathogens that would multiply in food, water, and milk in the hot weather. I mean, just imagine knowing that a diaper blowout could be the first sign that you’re going to spend the next few days watching your baby literally shit themselves to death. (Klass suggests that the sentimental, idealized deaths of angelic children in Victorian literature were a response to this particular horror–you could picture your child dying calmly, ethereally pale and beautiful, among clean white sheets, and then ascending straight to heaven, instead of what really happened.) Some antivaxxers today like to claim that improvements in sanitation were all we ever really needed to get child mortality under control–we start to see a drastic decline in child death at the time that cities and towns started working on providing clean water sources, sanitary sewers, and places where parents could get clean milk at reasonable prices, and antivaxxers like to suggest that, had no other developments been made, that downward trend would have continued. That is bullshit, because–as public health experts at the time realized–summer diarrhea was the low-hanging fruit of infant and child mortality. It was vastly more common in urban settings than rural ones, and more common in poor urban settings than well-off ones, so it wasn’t too hard to see the differences in those settings and identify some obvious contributing factors. And once they knew the causes, they had the technology to deal with them–it was just a matter of finding the will, and the money, to do so. Summer diarrhea was a very common cause of death in young children, and reducing it cut the mortality rate significantly–but it did little or nothing about any of the other causes of child death: the “childhood illnesses”–so called, because if you got them as a child and lived, you’d be immune–and ordinary infections (which could kill you even if the initial cause was as minor as a blister–that’s what happened to President Coolidge’s son). Society as a whole continued throwing money and effort at these problems because sanitation wasn’t enough. (It probably didn’t hurt that these were the causes of death that affected children from well-off families at similar rates as poor ones–a number of wealthy families funded vaccine research as a memorial to their dead children.) And the most recent efforts–the ones still ongoing today–have to do with care of premature infants and those with birth defects, and prevention of accidents and injury. (The book doesn’t really cover the treatment of childhood cancer and genetic diseases, which are also ongoing efforts, but aren’t traditionally considered “public health.”)The general trend in these efforts is that they started with the most common/most preventable causes of child mortality, and progressed to the less common/more difficult ones. This was deliberate–Klass even cites some debate among public health authorities, over whether the next stage after sanitation should be childhood illnesses or premature babies. Vaccines for childhood illnesses got priority, both because there were more children affected, and because it seemed easier. In the first half of the 20th century, child mortality was tackled–in a massive, coordinated, and expensive way–because it was a huge and devastating problem. Today, the leading cause of death for children is accidental injury, and we have the luxury of wondering if we’re doing too much to prevent it. -- source link

Tumblr Blog : whitepeopletwitter.tumblr.com